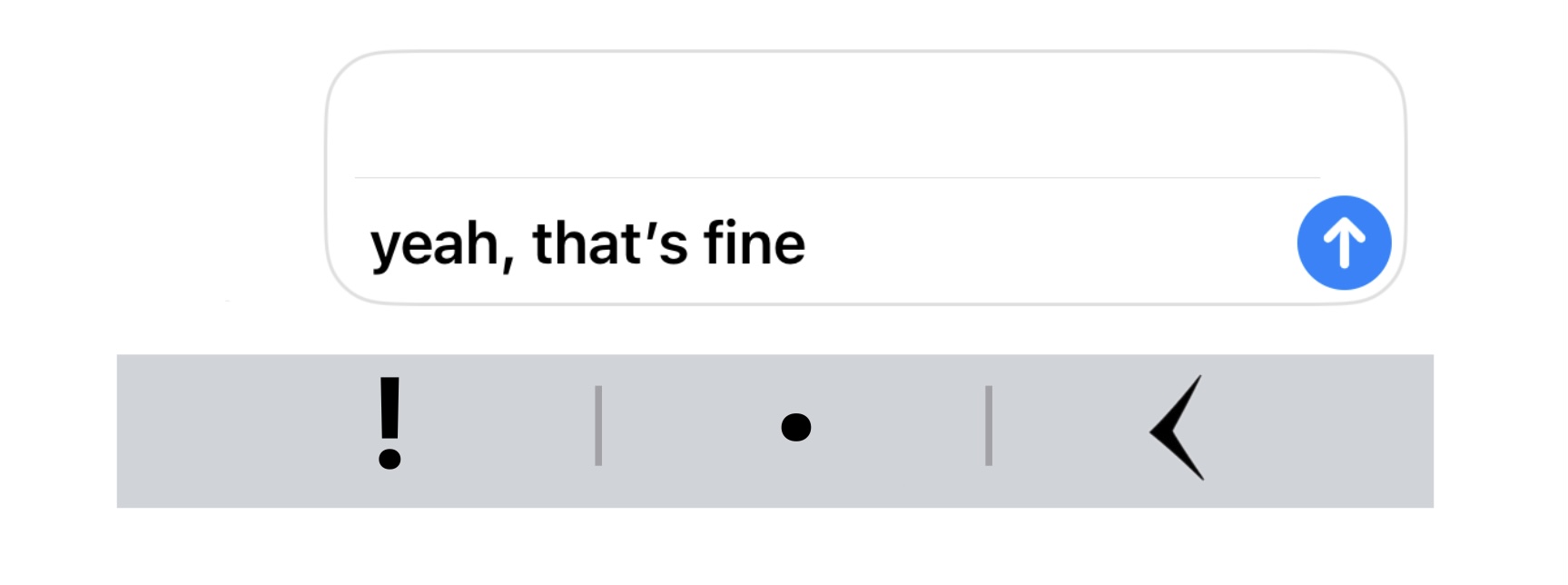

You can thank me later when this bad boy saves your current relationship. Graphic by Maddie Wood.

JOHN DUNN | OPINION COLUMNIST | jcdunn@butler.edu

Over the past week or so, many Butler students have lamented the notion that America is doomed. Or, at the very least, our proud democracy is beginning to show cracks in its foundation. I could not agree more.

However, my dismay toward the apparent degradation of society is not related to any particular recent, vaguely orange social phenomenon. Rather, I believe the greatest indicator that America is in trouble is the decline and fall of the period.

Periods have long held the distinction of concluding sentences that are neither exclamatory nor inquisitive and, thus, are by far the most used punctuation mark. If one were to anthropomorphize a period, it would be serene and laconic. However, it would also possess an air of justice and finality. It is truly the embodiment of benevolent neutrality.

This is at least what a period should represent. Unfortunately, it has increasingly fallen out of favor with college students and today’s youth. To many, the period has taken on a menacing or irritating quality.

This trend must be reversed, and there is only one viable solution — punctuation reform. But, before we can reform punctuation, we need to understand what is driving the shift to begin with.

Senior marketing major Ellen Kleyweg explained that the reason for the abandonment of periods stems from a concern about what the period now has come to imply.

“In text especially, I feel like [periods] are firm or angry,” Kleyweg said. “If someone says, ‘Yeah, okay period.’ It’s like my blood pressure is through the roof, and my heart is racing. Or even the word ‘fine,’ fine with no period; no problem. But if someone says fine with a period … someone is in trouble.”

Kleyweg is right that more people have begun giving the period a negative connotation but it should not be that way. Language is constantly changing and evolving, but there needs to be an underlying framework holding the language together. This framework provides the platform that allows language to be dynamic. The period is part of this fundamental framework, and tampering with the framework leads to confusion and disorder.

Associate professor of psychology Conor O’Dea also explained how the meaning associated with the period could have changed.

“I don’t think anyone really read into [a period meaning anything], until someone actually did look into it and pointed it out,” O’Dea said. “Then somewhere along the line, enough people start to think that maybe there is an emotion behind [the period], and then suddenly there starts to be an accepted emotion behind it.”

The passive-aggressive period when texting is a serious problem. Now that the period can be both neutral and angry, how is one to know which emotion the sender is conveying? The sender can even use the period ambiguity to their advantage by saying you are overreacting if you assume they are angry, or by saying they were obviously upset if you assume the period was neutral. Thus, they have the high ground no matter your response.

On the other hand, O’Dea also said that he enjoys the ambiguity associated with the period.

“The nice thing about the period is it gives the person using it a lot of power because it gives them the power to [express anger], it gives them the power to deny [that they expressed anger], and it gives them the power to say ‘You’re an idiot for believing that [I was angry.]’”

However, this interpretation of the period fundamentally changes what the mark means and how it can be used. Allowing the situation to remain unchanged puts pressure on the very foundation of our language. Instead, we need to be more ambitious — we need to introduce a new punctuation mark.

This new punctuation mark will expressly signal irritation, discontent or anger so that the period will be able to return to its job of being a neutral mark. I have even painstakingly detailed what the new mark will look like by scrolling through the list of symbols on Google Docs and selecting the symbol that most resembles a pair of angry eyebrows — the old Persian symbol for 10. It can be used as follows: “I can’t believe Butler men’s basketball lost to Austin Peay𐏓”

I have named the newest member of the punctuation family the malign mark. It fits nicely next to the exclamation mark and the question mark in the repertoire of emotion-denoting punctuation. Using the malign mark is the grammatical equivalent of letting out an overdramatic sigh or shutting a door slightly too aggressively when leaving a room.

This mark will transform both text communication and literary writing. In texting, it replaces the passive-aggressive period, reduces unnecessary confusion and, to some people’s dismay, encourages healthy communication. For journalists and authors, it offers a fresh way to convey tone, making scenes and emotions more vivid. The malign mark could even pave the way for more emotion-driven punctuation in the future.

Senior accounting major Ben Rohn shared his thoughts on the implementation of the malign mark.

“I think in modern texting, [periods] have gotten to the point where they convey a sense of anger,” Rohn said. “However, I believe the period should go back to being a neutral sentence-ender. Right now, if I wanted to convey irritation, I would use capital letters or an exclamation point. But, if there was a different mark for irritation or anger separate from the period, that would be ideal.”

Some may argue the malign mark is unnecessary, suggesting that using no punctuation is perfectly fine — and historically backed. Cicero, Rome’s greatest orator, famously despised punctuation, insisting a speaker’s skill should guide the flow rather than punctuation.

However, 21st-century period deniers likening themselves to Cicero should tread carefully; his speeches occurred as the Roman Republic collapsed and became the Roman Empire. I am sensing a trend. Is it a mere coincidence that our own American republic’s political tensions are on the rise as the humble period fades from use?

On a more serious note, the malign mark will genuinely be beneficial to the literary community. Firstly, it will add a new level of flavor to conversations. There are an untold number of human emotions, but we only have three punctuation marks with which to convey all of those emotions — two if you consider the fact that the period’s effectiveness has been neutralized.

Critically, the malign mark will also remove the confusion and ambiguity currently associated with the period. Now you know that when your mom says, “We will talk at home.” you aren’t in trouble. If you were in trouble, she would say, “We will talk at home𐏓”

In both formal and informal writing, the malign mark has the potential to be the most significant development in English grammar since we learned that saying “thou” unironically isn’t cool. The period is overworked and misused daily, and, as a literate population, it is time to increase the diversity of sentence-ending tools at our disposal. The period deserves a break, and if you don’t think so, you’re part of the problem𐏓