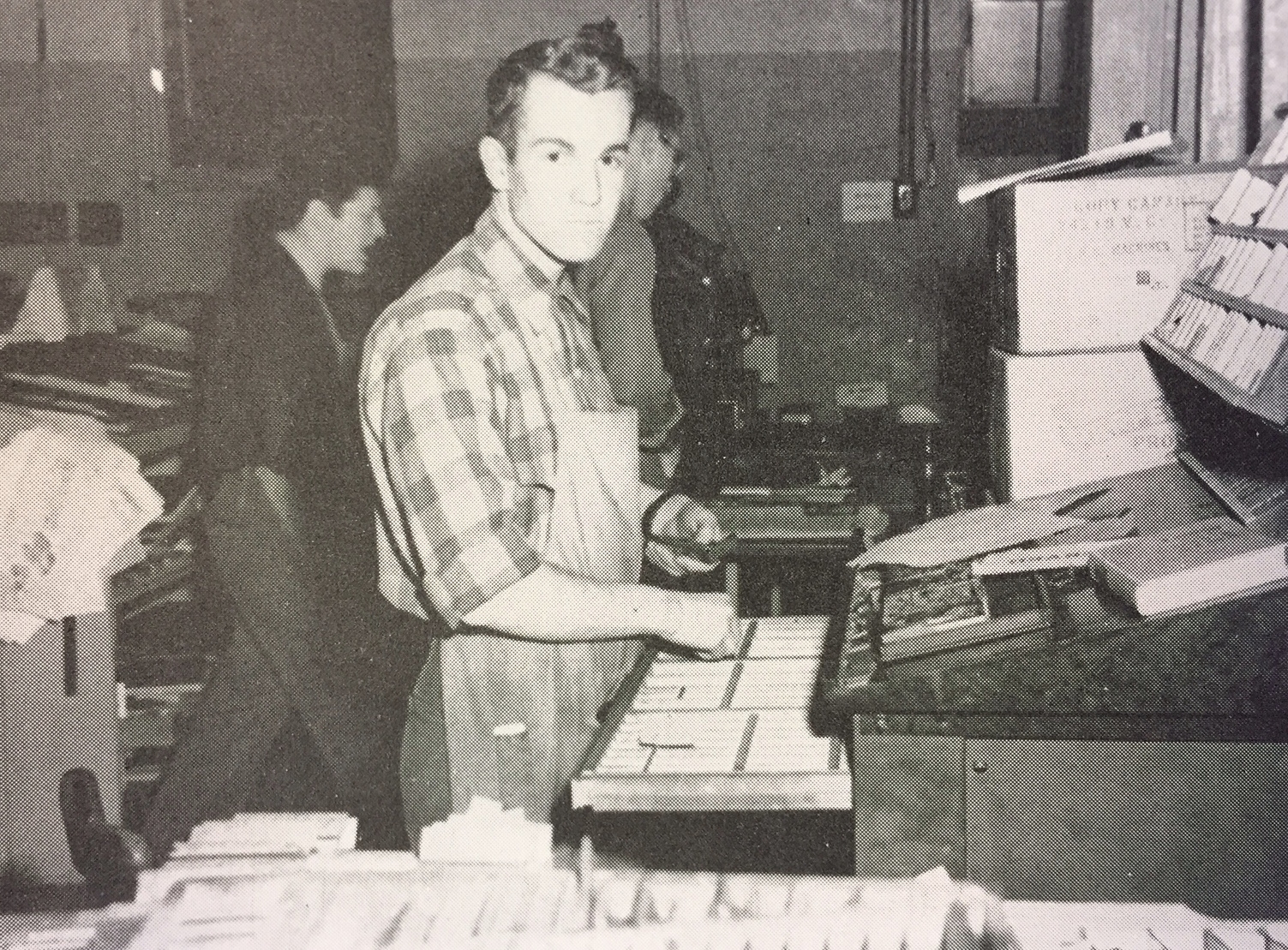

Max Schumacher during his time as a business manager for The Butler Collegian. Photo from 1953 Butler yearbook.

DANA LEE | STAFF REPORTER | delee1@butler.edu

The high school baseball coach at Shortridge High School gave the sales pitch to Tony Hinkle. Max Schumacher was a solid local ballplayer — any chance he could get a scholarship playing for Butler?

Schumacher knew the finances for tuition would be tight, but never thought about going anywhere else. His parents were students when the campus was located at Irvington, and his two sisters went there as well. He would live at home to cut costs at a time before government loans and financial aid.

Which is why during his senior year in the spring of 1950, his baseball coach was talking to Tony Hinkle. The man sat on a chair, Schumacher and Steiner on a nearby training table.

“Mr. Hinkle did this terrific — soft shoe, I call it. A dance, a verbal dance,” Schumacher said.

“Well kiddo, we have a wonderful school here,” Hinkle said. “You just start in, you go to class, take your academics seriously and we’ll have a call for baseball. And away we go!”

In other words, forget the scholarship, kid.

“And away we go!” Schumacher murmurs the last words again. “I’ll never forget that.”

He doesn’t forget much. Time, it seems, is one overlapping measure into the next.

“He’ll start telling a story from something that happened 30 to 40 years ago that’s really interesting, and I don’t think he thinks it’s as interesting as it really is,” his son Mark said. “He’ll tell stories and I’m like, ‘Well, I’m just hearing this for the first time, why haven’t I heard of this?’”

One story in particular marks the beginning of all other stories. It was 1957. Discharged from the military, Schumacher walked into the office of the Indianapolis Indians’ general manager. In Schumacher’s hand, a single scrap of paper scrawled out by the team owner:

“This is the young man I talked to you about for the ticket manager position for the Indians.”

One sentence stretches into 60 years with the minor league baseball team. The ticket clerk became his wife, even though neither of them saw it at first.

“She’d know more about the office than I did, and she didn’t mind telling me about that,” Schumacher said. “That doesn’t promote romance, I guess.”

But she understands the demands of baseball. They watched Starlight Musical’s production of “Damn Yankee,” on the south of the Butler Bowl on their first date. Their four kids grow up at the ballpark. Two sons still work there.

The years fold into one wrinkle of time. Schumacher became the Indians’ publicity director in 1959, general manager in 1961 and president eight years later.

He liked to work on Saturdays when the team travels, because the phones are quiet and the park is empty. He does this at Bush Stadium, and when the team moved to Victory Field, he liked the quiet there, too.

Schumacher did all the team’s billings before computers. Each sponsor had installment plans in files, typewriter clacking away. Radio billings finished, he’d come home. A week or two later and the billboard files went through the same process.

“Work has been such a central part of his life, that he expected to work long and hard all the time,” his son said. “He never thought, ‘Well, I’ve worked long and hard for 10 years, now I’m entitled to work less.’”

The Indians became one of the most profitable minor league teams in the country. He rejected offers to work in the front office of major league teams like the Seattle Mariners. He was intrigued, but not enough. Watching his team win championships was like Christmas morning.

Under Schumacher, the organization emphasized affordable family fun and excellence on all fronts. Butler senior Jordan Galligan, a former intern with the Indians, saw it firsthand.

“He’s a guy that in his presence, you feel he’s been around the block,” Galligan said. “You feel the respect. And it’s a mutual respect. He’ll respect you even if you’re an intern. He’ll still give you the time and day as if you were a full-time employee.”

Walking along the curved pathway at Victory Field, interacting with fans on gameday, Schumacher found it easier than listening to road games on the radio. It was nerve-wracking not being able to see the game.

The first time it happened, Schumacher kicked a toy race car across the living room after the team let up a lead in the 9th inning. From then on, his son, a toddler at the time, placed a nerf football in front of his dad during broadcasts. It never happened again.

And when former Butler President Bobby Fong called to say he’d been inducted in the school’s class of 1998 athletic hall of fame, Schumacher did his best to persuade the president otherwise.

“I was on the team, but I was not a great athlete. You might be diminishing the stature of the hall of fame if you put someone like me in,” Schumacher told Fong.

He coached third base more than he played at second, simply because that’s what Hinkle told him to do on opening day as a freshman. Hinkle gave the signs from the dugout, but until his senior year, Schumacher was the one waving players to home or stopping them at second.

He wasn’t even supposed to dress for that game. He wore an extra uniform the equipment manager found.

“It didn’t match the others,” Schumacher said. “But I had a uniform that said Butler on the chest.”

When he was younger, his father dropped him off at 16th Street to stand in line for Indianapolis Indians tickets while the senior Schumacher parked.

“I would begin walking,” Schumacher said. “But when I’d get halfway there I’d break into a trot and then finally I’d be running when I got close to the ticket windows. I can’t explain it very well, but the ballpark kind of served as a magnet.”

Decades later, his son Mark peered down Victory Field’s parking lot, watching his father walk to Lucas Oil Stadium for the 2010 Butler NCAA Final Four game. If the man in his eighties could jog, that’s exactly what he would be doing.

His son remembers one Butler basketball game in particular. The snow was blinding, stopping cars on the way home. Mark watched his father get out of the car. He started directing traffic, and the cars rolled down the street.

“I’ll always remember that,” Mark said. “In hindsight, it seems crazy, but at the time it seemed like something he would do.”

His figure silhouetted by headlights, swept in the white of snow and black of night. The way cars followed, the winding motion of his arms signaling it was OK to cross.

So they followed. The boy who walked then ran to ballparks, waking up to check the box scores in The Indianapolis Star, who thought he might work at the newspaper one day, but read a paragraph-long article about a job opening with the Indians instead.

He makes baseball one giant reunion between generations of time. A weekend home stand — the bat cracks, the ball sways foul and the crowd swells, a hand reaching out. A father hands the ball to his child, moments created by the confines of the ballpark Schumacher helped build.

He’s the young man who walked into the ticket office with no real plan after the army, and the same man who left work one day realizing that it’s been close to 60 years since.