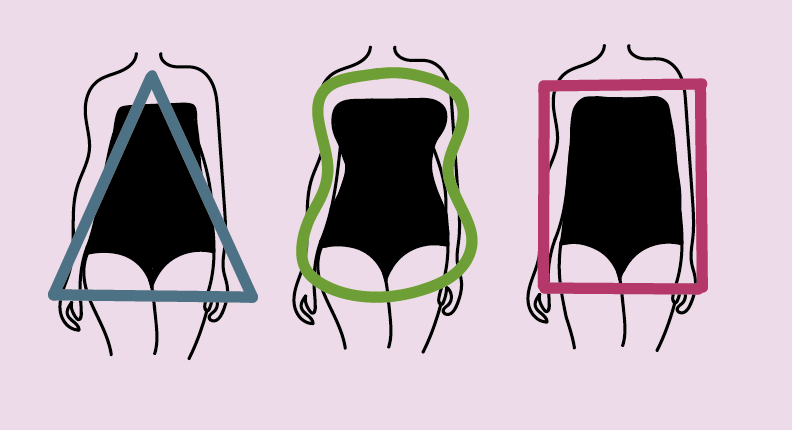

Each decade ushers in new trends, but trends applied to bodies can particularly shape identity. Graphic by Elizabeth Hein.

ABBY KIDWELL | STAFF REPORTER | arkidwell@butler.edu

Content warning: Discussions of body image.

Many unstoppable cycles occur in life, such as the phases of the Moon or the spin of the Earth on its axis. Like environmental cycles, cultural cycles also exert a powerful pull — especially the trend cycle.

A music genre might dominate for a few years before being usurped by something fresher. What was cool five years ago is likely not cool now. Clothing, makeup and even bodies are all unfairly subjected to the whims of what is considered “in” or “out” at a specific moment in time.

Typically, people can choose whether or not they want to participate in a trend, but in the case of body trends, no such freedom exists. What is considered the ideal body has shifted from decade to decade.

Renaissance art depicts women with rounded shapes. In the 1920s, having a slender, boyish figure was all the rage. The body positivity movement in the 2010s encouraged unconditional self-love, but an underlying preference for women with small waists and large butts existed. Now, in the 2020s, a new body trend that prioritizes slimness is taking form.

Senior sports media major Gaby Whisler has witnessed this evolution firsthand.

“Growing up in the 2000s … the main culture was to be as skinny as possible,” Whisler said. “In high school and my early years of college, it definitely [changed] to body neutrality and body positivity, which I think made a lot of people feel accepted in their own skin … Now, I feel like [we have] been going back to that early 2000s mindset.”

The return of Y2K fashion staples such as low-rise jeans and microskirts was undoubtedly a symptom of this shift. The public has also speculated that Kim Kardashian, who became known for her curvy body type, has lost weight to stay relevant in the changing climate.

Junior classics major Abby Ruble attributed the return of the thin ideal to the increasing availability of GLP-1s, specifically Ozempic, which are medications that lower blood sugar and promote weight loss.

“A few years ago, there was a very large trend of ‘All bodies are beautiful,’” Ruble said. “There were plus-size models, and everybody was like, ‘Having hips and being big is great.’ And then Ozempic came out.”

Although appetite suppressant drugs are far from new, Ozempic has captured an unprecedented level of attention from the media since 2021, when the active ingredient was approved for weight loss. People went viral on social media for chronicling their experiences with the drug, adding more fuel to the fire.

TikTok serves as a vehicle for the changing trends by playing host to a variety of content that is either subtly toxic — like “What I Eat in a Day” videos — or blatantly toxic — like body checking. Some influencers have built their platforms by sharing their best tips on how to get skinny and stay skinny. Other wellness pages, especially fitness accounts, encourage detailed tracking of every calorie consumed, a habit that can result in an unhealthy fixation.

Whisler noted that while standards for female bodies are enforced to a greater extent, male bodies also face scrutiny and pressure to conform.

“With men in our generation, there is a big emphasis on gym culture and building muscle,” Whisler said. “You have to hit the gym every day and eat 200 grams of protein. It makes you think you are doing everything wrong if you are not doing exactly what they say.”

For many, weight comes to mind when they hear the term “body standard”. In reality, this term encompasses societal norms concerning diverse attributes, such as facial features and skin tones. Social media can contribute to the dissemination of unrealistic expectations. Every day, users scroll through videos dissecting celebrity photos for signs of rhinoplasty or botox and presenting trendy cosmetic procedures as a cure-all to life’s woes.

Avery Terry, a sophomore history and German double major, suggested that the proliferation of plastic surgery is resulting in a widespread loss of individuality.

“In the 90s and early 2000s, if you watch romcoms, everyone has a really unique face, but now, everyone has the same veneers and [has gotten] buccal fat removal,” Terry said. “Everyone [has started] to look similar.”

In response to increasing pressures to look a specific way, a new movement has arisen: body neutrality. Rather than existing at the extremes of self-love or self-hatred, body neutrality posits that physical appearance is actually the least interesting thing about a person. Instead of focusing on what a body looks like, one can focus on what that body can do.

Ruble is a strong advocate for body neutrality.

“You are more than your body,” Ruble said. “You are also your personality. You are your friends. You are your connections. You are what you love. You are your hobbies. You are so much more than the physical space you take up.”

In a culture that values aesthetic attractiveness first and foremost, distancing oneself from that idea is both an act of revolution and self-acceptance. The only way to escape the rigid, imposing and reductive nature of body trends is to deconstruct the idea that value is based on appearance rather than character.