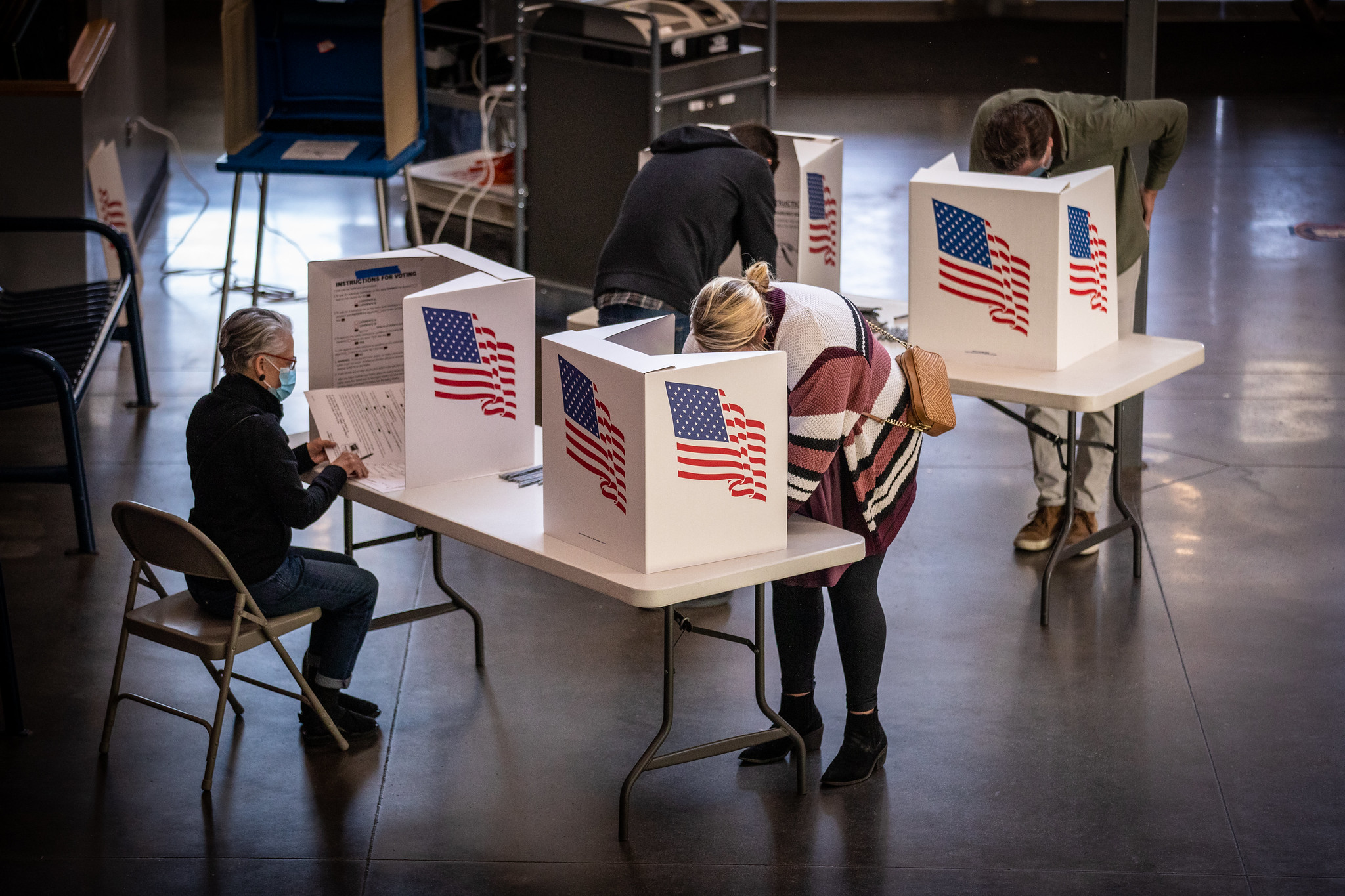

Students historically hit the polls at a lower rate than the general population. Photo courtesy of Phil Roeder.

JOHN DUNN | OPINION COLUMNIST | jcdunn@butler.edu

What does it mean to be disenfranchised? The commonly understood definition of disenfranchisement is to lose a right or privilege; it is most commonly used in reference to voting. Such a definition implies that disenfranchisement is a binary — either you have the right to vote and are not disenfranchised, or you don’t have the right to vote and are disenfranchised.

The reality is — as is often the case — more nuanced. Rather than being a binary, American history suggests disenfranchisement is a spectrum, with entirely unimpeded access to voting on one end and a total prohibition of voting on the other. For example, following the passage of the 15th Amendment, all African American men theoretically had the right to vote. However, in actuality, many African Americans were denied at the polls due to the Jim Crow laws that intentionally increased the difficulty of voting on the basis of race.

These laws did not expressly disenfranchise a certain population from voting — as had been the case before the passage of the 15th Amendment — but did intentionally implement disproportionately large barriers to certain groups’ abilities to access the polls. Today there are still groups that face more — less extreme — barriers when voting than others. These barriers are well documented in modern politics, even if the term disenfranchisement is not often used. A law may be criticized as having a suppressive or demobilizing effect on voters. If a law or policy has a demobilizing effect, it is simply moving a group further away from the “unimpeded access to voting” end of the disenfranchisement spectrum.

Using this understanding of disenfranchisement, college students are one of the more disenfranchised populations in the United States.

Assistant professor of political science Rhea Myerscough sees the disproportionate burden college students in her classes face when going to vote.

“There are two things working against college students,” Myerscough said. “First, [college students] are just starting to vote, so you’re learning how to navigate the terrain for the first time. [Second], you have to decide: ‘Where am I voting?’ ‘Do I have to go back home?’ ‘Can I absentee vote?’ The registration [and long distance voting] processes present a bigger burden for younger people, especially college students.”

As a largely displaced, poor and inexperienced section of the population, college students find it difficult to find time to go home and vote or navigate the absentee voting process. In Indiana — for example — voters must vote in the county in which they are registered. If a Butler student is registered to vote in Fort Wayne, they would have to make the drive home, rather than being able to vote at a local polling place in Indiana. Unfortunately, going home for one day in the middle of the week is unrealistic for most students, even more so for out-of-state students.

The alternative to going home to vote is absentee voting. While the process of absentee mail-in voting typically depends on the state, the process involves multiple steps. First, as is the case in Indiana, a person must fill out a form where they will provide a reason why they are requesting an absentee ballot and provide verifying or other general information.

Secondly, the student must also either update the mailing address on their voter registration or have their family mail their voter package after it gets to their house. Finally, the student must check the mail-in voting rules of the state they are registered with to make sure they are compliant.

The process of absentee voting is not impossible; millions of Americans do it every year. However, with the potential to mess up at various points during the multi-week registration and absentee voting process, many students — who are already among the most stressed and anxious populations in the country — decide that voting is not worth it. In the 21st century, disenfranchisement is not an outright prohibition on voting. Rather, disenfranchisement occurs when the voting process is made difficult enough that people opt to just stay home.

Spencer Seigworth, a senior risk management and finance double major, is a proud resident of Phoenix, Arizona. However, he is now navigating the process of figuring out how to vote despite being thousands of miles from home.

“This will be my first time filling out a mail-in ballot,” Seigworth said. “I’ve contacted my family, and once they receive my ballot, they are going to send it to me. Hopefully, I’ll be able to [fill it out] in time. It’s just inconvenient, having to go through the extra hurdles. Definitely, for the non-presidential election, it was kind of an inconvenience … and that’s why I missed [voting] two years ago.”

Spencer’s experience is a common one. For demobilized groups, including college students, restrictions and barriers to voting have been a common theme. They have often even been incorporated into the political strategies of politicians and political parties.

Assistant professor of history Molly Nebiolo spoke about the history of voting in America, and about how barriers were established to consolidate power among certain groups.

“[Americans] don’t want the men that we put on a pedestal to be blamed, but there was a lot of selfishness in the room when the Constitution was being written,” Nebiolo said. “If we look at the demographics of most of the men who helped draft the Constitution … broadly speaking they are rich white men who owned land. They knew, even though they were pushing for a better life, now is the time … for them to structure their new country in a way that benefits them the most.”

In addition to the legal restrictions placed against certain groups, Nebiolo discussed how voting barriers were implemented in more subtle ways as well. For example, information about voting would only be pronounced via pamphlets to exclude the certain groups. From the beginning of the American Republic, voting has always been a privilege afforded to those who have the time, resources and connections to take advantage of it. So, college students facing an uphill battle to make their voices heard is the modern incarnation of a tradition stemming back to the advent of our republic.

It would be unfair to retrospectively criticize the writers of the Constitution too harshly. A republic with some barriers to voting is still radically progressive compared to the autocracies common in the period. The U.S. Constitution has also served as a template for most modern democracies across the world today.

That being said, the lingering effects of a system designed 250 years ago to subtly, and in some cases not-so-subtly, influence different group’s access to voting are still present. The United States is one of the few functioning democracies that does not guarantee time off to vote. Most democracies automatically register their citizens when they come of age, while the registration process in America dissuades many potential voters. Additionally, most democracies have standardized voting procedures across states and provinces, while discrepancies between American states cause confusion.

The word disenfranchisement is very politically charged. Some would also say calling college students disenfranchised is an over-exaggeration. It is true that today college students are very far from the most disenfranchised voting group in American history. It is also true that in most cases, none of the challenges college students face are insurmountable.

However, many Americans operate under the assumption that today, everyone has equally easy access to the voting polls — which is not the case. The challenges that college students face when casting their votes are a microcosm of the challenges that are faced in varying degrees by many communities.

Solving this problem is no simple task, but a few natural next steps are apparent. Firstly, standardizing the voting system across states could reduce confusion and make out-of-state voting easier. Even if states are unwilling to adopt a federally mandated system, efforts should be made to standardize how out-of-state votes are collected and processed.

States should also consider implementing automatic voter registration or allowing same-day registration, both of which would ease the process of getting to the polls. Additionally, increasing the number of polling locations, rather than reducing them, will ensure voters have easier access to nearby polling stations. Lastly, making Election Day a federal holiday could be one of the simplest yet most impactful solutions, giving every American the opportunity to vote.

It is inaccurate to say that access to voting hasn’t improved drastically since the implementation of Jim Crow laws and the total disenfranchisement of women. That being said, it is also dangerous to assume that disenfranchisement is a non-issue in the 21st century.

Voting has always been a right for people who have the time, education and resources to access it. While resources and education are at an all-time high, the inability of certain groups to access the polls still has the potential to swing elections. Since 2021, nearly half of American states have enacted laws that make voting more difficult, and the number of polling locations available to Americans for the 2024 elections will have dropped by nearly half.

There are no current barriers that cannot be overcome by most determined voters, but that is not the point. It should not take a herculean effort to make one’s voice heard. The more difficult it is for someone to vote, the more disenfranchised they are. Right now is likely the period in American history with the lowest number of disenfranchised people, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for improvement, or that progress made up to this point is irreversible. For proof, just visit your nearest college campus.