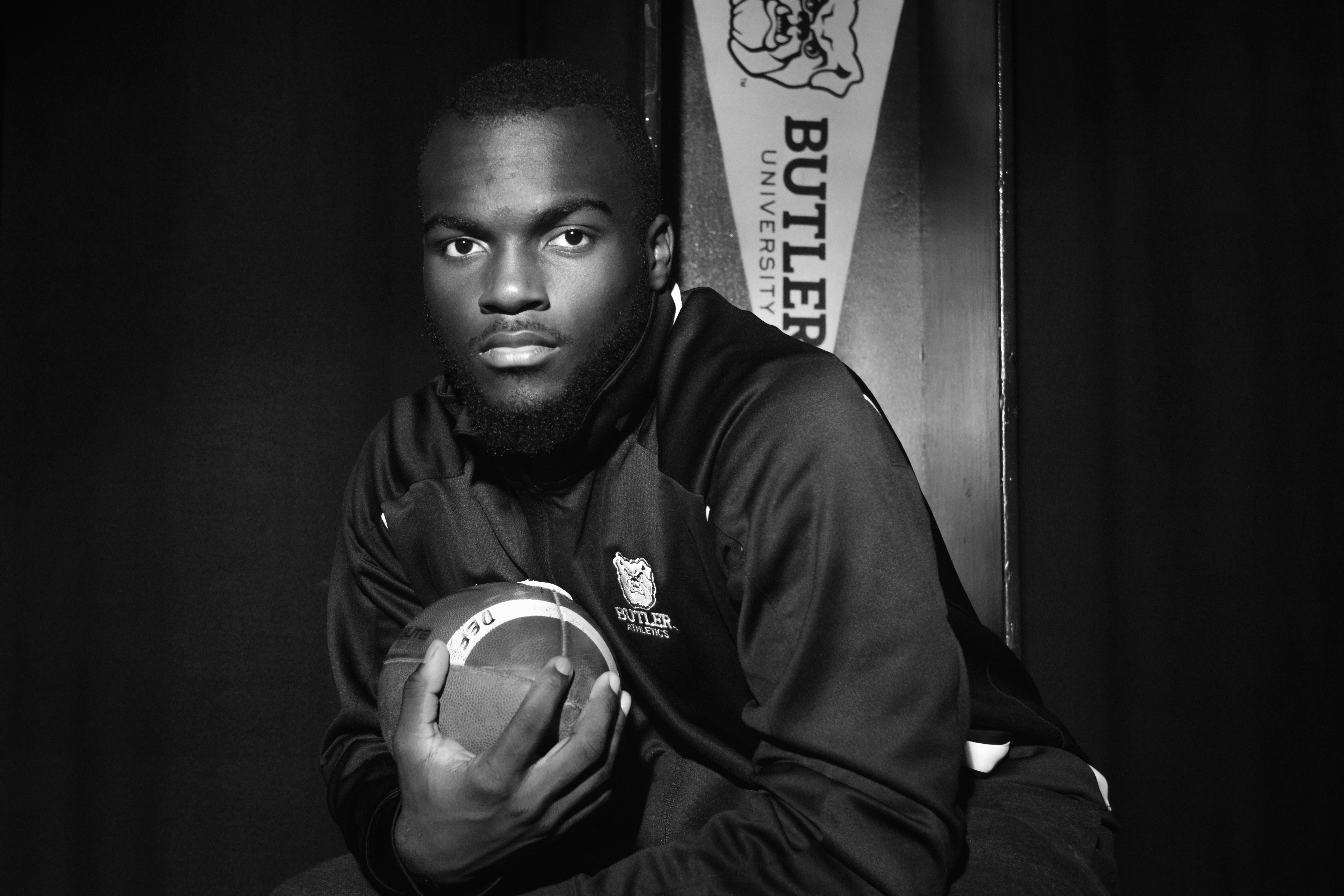

Xavier Colvin came out to his teammates this past summer. Colvin is a middle linebacker for the Butler football team. Photo by Dana Lee

DANA LEE | SPORTS EDITOR | delee1@butler.edu

Xavier Colvin is in the the basement of Hinkle Fieldhouse watching film Monday through Friday. He can pick up on almost any team’s offensive patterns if he watches the film long enough.

Every opponent has a tell. Sometimes it’s a glance at the offensive lineman’s hands. Fairy fingers, his high school football coach called them, when the knuckles don’t quite hit the ground, and it’s just enough to tell whether the offense will pass or rush.

He has less than five seconds to reevaluate where he’s going to meet the ball. Colvin’s arms cross over his chest by habit, upper body leaning forward in his seat, and the projector beams just enough light to catch the way his eyes track across the screen. There it is. The tight-end is almost a dead giveaway, and the team will run the ball almost every time.

The middle linebacker mastered the middle ground, a sliver of space measured by compromise and sacrifice. Here, somehow, maybe, he could keep everyone happy.

He could be the football player he wanted to be and the gay man he needed to be. But to be both at the same time?

“It felt like I was a caged bird,” Colvin said. “I couldn’t be me 24/7. I had to be two-faced. Not in a bad way, like I was being fake, but I was. I was faking a lot of things, faking a lot of emotions, faking a lot of actions.”

Some days it felt like there was hardly any ground beneath his feet, just a strip of earth thinner than the 50 yard line. The edges kept retreating. The hiding and faking — it sucked the air right out of him, worse than any tackle he sustained on the field.

“Beggars can’t be choosers.” Wasn’t that what his mom told him? Only in this case, it hardly felt like he was in a position to beg for anything. Playing college football, couldn’t that be enough for now?

Xavier the linebacker could be enough. He could be enough for his team. He danced during practices, a one man entertainer during “Soulja Boy,” and was the one yelling at morning practice when everyone else was still waking up.

He was exhausted.

“If I didn’t care about the relationships I have with my teammates and coaches then this would’ve been easy,” Colvin said. “But I do and I never want to make anyone uncomfortable and as weird as that sounds, I’ll put other people’s comfort ahead of my own.”

It was subtle. Nine months ago he changed his Twitter bio, copied from Nike’s campaign for LGBTQ equality. #BeTrue.

He tries to find middle ground, in Indiana of all places, and it’s just too hard some days, to hold claim over this island when his father’s name is synonymous with Indianapolis sports. Rosevelt Colvin, a Broad Ripple High School and Purdue alum, two-time Super Bowl champion with the New England Patriots.

It doesn’t matter where Colvin is — street, restaurant, park — people stop him in Indy. “Little Rose! Doesn’t he look just like his dad?”

Maybe he could’ve done it, swallow the pill without batting an eye and play through college without being known as the gay football player. He made it all the way through North Central High School without telling anyone besides family. Who’s to say he couldn’t do the same at Butler?

Maybe it would’ve played out just like that, if he hadn’t met the Butler athletics academic advisor his freshman year. The school hired Carly Dressler three years ago in July. She was new on campus and so was he, and when he walked into her office for the first time, “Carly Cares” was looped in a bubbly font across the whiteboard in the corner.

His freshman year she’s the first person on campus he tells, and when she only shrugs and says “OK,” he’s taken aback. She had to have known. He thought he was good at hiding the fact but what if he’s the only one being fooled here? Carly reassures him. No, she didn’t know.

It was a bombardment of reinforcement from Carly.

“People love you for you,” she said looking at him, and it was hard not to notice the same message on the whiteboard. Carly Cares. “This doesn’t change who you are, this changes nothing about the fact that you care about people and you’re a good human being, you have your values and morals, it literally changes none of those things.”

Colvin flipped her argument. “How can they really love me, if they don’t know this part of me?”

It’s hard to imagine they were ever strangers, like he’s always been there, and she has always laughed at his jokes. “Kevin Hart-like” is what she calls his humor. He floods his housemates’ group messages with Twitter memes until they roll their eyes toward the ceiling in exasperation. “X, oh my God.”

If he’s being honest, Colvin’s teammate Alex Lozon doesn’t even remember what the text said. His friend was gay. OK then.

“It was really kind of an unremarkable moment which I guess is good because as we move forward through history it needs to be less remarkable that people are gay,” Lozon said.

It was Colvin who drove Lozon to the airport after his grandmother died. No way he was going to let Alex take an Uber. He had that look on his face, the same one he has when they’re grocery shopping, and Colvin has to smack Alex’s hand before he can reach for an item of the shelf. Are you crazy? The exact same thing is on sale to your right.

The text doesn’t change a thing, and it gets easier to set aside the butterflies long enough for Colvin to send several more to the leaders of the team. The business major inside him reasons football is like any other company. It works top-down, and everyone else will fall in line.

Colvin told the coaches last spring. Linebackers coach Derek Day told him all he needed to hear, even if he didn’t believe all of it at the time.

“Xavier, this is nothing different than you telling me your eyes are brown,” Day said. “Don’t take this personally, but it’s not that big of a deal.”

It was everything he could’ve hoped for and all at once, not nearly enough. So, it didn’t stop. The weight lifted off his shoulders when he told the entire team during the player panel they hold every summer camp. He held the paper in his hand, with the four typed out questions they gave to every player speaking. Mostly so they don’t ramble. It was the last question. What have you learned from being at Butler?

“For those who don’t know me or have really been too caught up in my personal life and I haven’t told you, I’m gay.”

He never wanted to be the crusader for gay football players.

“Finally I got to the point where I wanted to be for a while,” Colvin said. “The room was — I had the floor, I took a look around and it was like, I knew I could do this all along but it just took me a little while to get here.”

There’s kid in Colorado. Someone show him how to do this, because he’s 15 years old and learning how to drive a car, but no one’s telling him how he can play football and be gay. This is a kid in Colorado we’re talking about, but we’re not. He’s the running back for a high school team in Iowa, a cornerback in the Los Angeles inner-city school system. He can be a wide receiver from Arkansas practicing his routes. And on the East Coast too, they need to know they’re not alone.

They’re not. Colvin hopes they know that now.