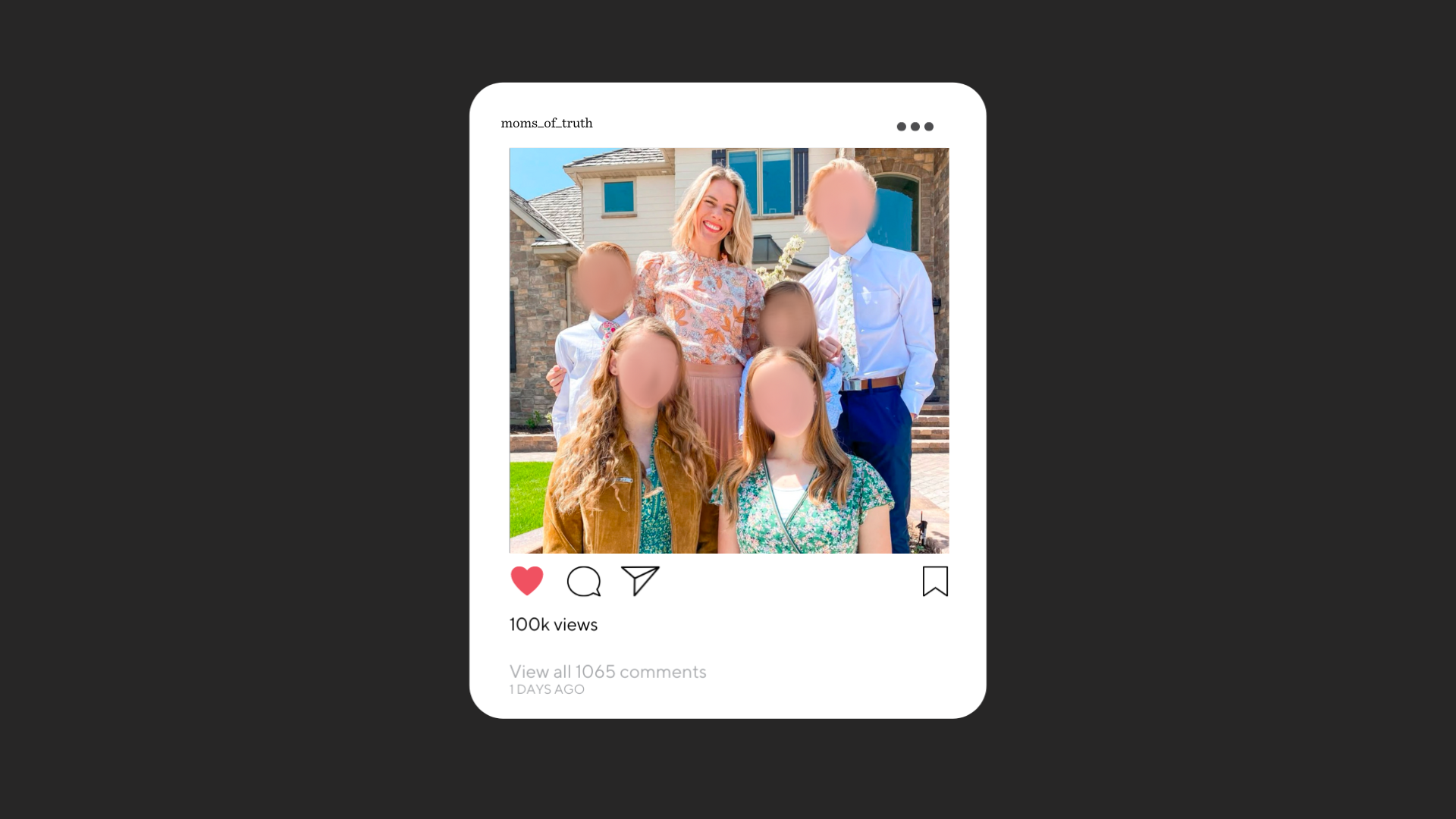

Everyone takes videos of their kids’ special moments, but not everyone has to post them. Photo courtesy of moms_of_truth on Instagram and graphic by Anna Gritzenbach.

TESSA HAMILTON | OPINION COLUMNIST | tehamilton@butler.edu

In the 21st century, we are blessed with every form of entertainment imaginable right at our fingertips. Most notably, we have YouTube. Whether your thing is video essays, podcasts, prank videos or “How it’s Made,” plenty of Gen Z have a guilty pleasure YouTube channel they watch when they’re feeling down.

While YouTube can be incredibly tame most of the time and even beneficial on occasion, some of the content that appears harmless and helpful can often be deceiving. Family vloggers are a topic of discussion now more than ever. I’ll admit, I was a Bratayley fan back in the day, and still today often have a curiosity about what family vlog channels are popular — and their controversies.

These channels are nothing less than exploitative. Making online content of yourself — while frowned upon by some — is one thing. Making content of your children, especially when they are too young to consent, and taking the earnings for yourself is an entirely different issue.

Not only do family vlog parents often prank their children for views, exploit them for money and embarrass them to an audience of millions, but there are multiple cases of gross things happening behind the scenes.

Lorelei Guenther, a first-year middle-secondary English education and English double major, expressed concern about how these accounts can influence young viewers.

“I think sometimes these accounts reward bad behavior in a way,” Guenther said. “[The videos are] like ‘This funny thing my child did,’ but it was bad behavior, and that might influence other kids to behave in this way.”

Many pages on TikTok post videos of their children that can be taken incredibly inappropriately, and thus share their children with predators on the Internet with every click of the “Post” button. Videos like a child playing with a tampon or taking a bath, attract higher numbers of likes and saves than other videos featured on the same pages, as well as comments from middle-aged men on how “beautiful” the child is. Autofill search results, influenced by other TikTok users’ common searches, request videos of this child “eating a corndog,” or “wearing scandalous outfits.”

Junior criminology and psychology major Molly Goodman did a research paper on the subject of the account of wren.eleanor on TikTok, which is an account that has received backlash for the mother posting her “kidfluencer” in situations easily sexualized.

“[The comments] are all gross, and [Wren’s] mom is aware of it and lets it happen,” Goodman said. “Her child is on the dark web, and who’s protecting [her] … and that is a very sad fact. It’s not our fault that predators use things inappropriately, but we do have a responsibility and duty to protect these children from future harm.”

Notably, the minimum age requirement for TikTok is 13-years-old. Despite this, by making accounts run by parents, these accounts centered around a child are able to bypass such restrictions.

Bex DeMarco, a first-year history and political science double major, described their discomfort with certain types of content posted with children.

“There’s a huge issue [with it],” DeMarco said. “I have always thought that it was so stupid that people would willingly put their kids out there, receive these comments and not be grossly alarmed and delete the content to protect their children.”

With recent news, many have heard about Ruby Franke’s abuse and the infamous 8 Passengers YouTube channel. After making her presence online starting with the birth of her youngest, Franke would vlog her children’s entire lives. When her youngest son, Russell, came to his neighbor’s house bloodied and bruised, the police raided the home that Franke and her friend, Jodi Hilderbrand, were living in. They found signs of horrific abuse against the children, and things only worsened with the children’s testimonies. However, even before the evidence of abuse came out, signs of exploitation and ill-treatment of the children were apparent. Ruby would often post embarrassing videos with her kids, including bra shopping and discussions of their struggles and friendships.

Ruby’s mistreatment of her oldest son Chad, is, in the vlogs, by far the most apparent. She sent him to wilderness therapy when he was expelled from school. When he returned, he pranked his little brother, and she reacted to this by taking away his bed for 7 months.

Shari Franke, who recently released a memoir detailing her experiences with her mother, was told she would be kicked out of the house as soon as she turned eighteen. On the day of her birthday, 8 Passengers uploaded a video titled “Happy Birthday! Pack Your Bags!”

Goodman explained that the case brought against Franke could bring some positive change.

“I think this case really opened a lot of people’s eyes,” Goodman said. “We should always keep an eye out on these family vloggers and anybody who ‘sharents.’ Somebody has to be there for those kids. If their parents aren’t going to protect them and they’re going to exploit them, somebody has to protect them.”

Now obviously, the harm of these influencers is not the fact that they’re simply posting their kids, it’s that they’re posting their kids to thousands of people and making money off of it. It has been proven time and time again that fame can make the general public ignore that someone is a bad person, and this rings just as true with family vloggers.

We’ve now seen the worst-case scenario of these channels, with the court cases and evidence brought against Ruby Franke being examples enough. However, the issues at hand can sometimes be far more subtle, with secretive catering to predators and the use of controversy to increase views and profit.

Although the average person doesn’t have a YouTube or TikTok channel with millions of followers, the practice of safe social media usage is never a poor idea. Parents and friends alike should be incredibly wary of what they share about their children online for fear of more individualized versions of these broad concerns.

And please, don’t name your future child “Orange” because you think it sounds unique.