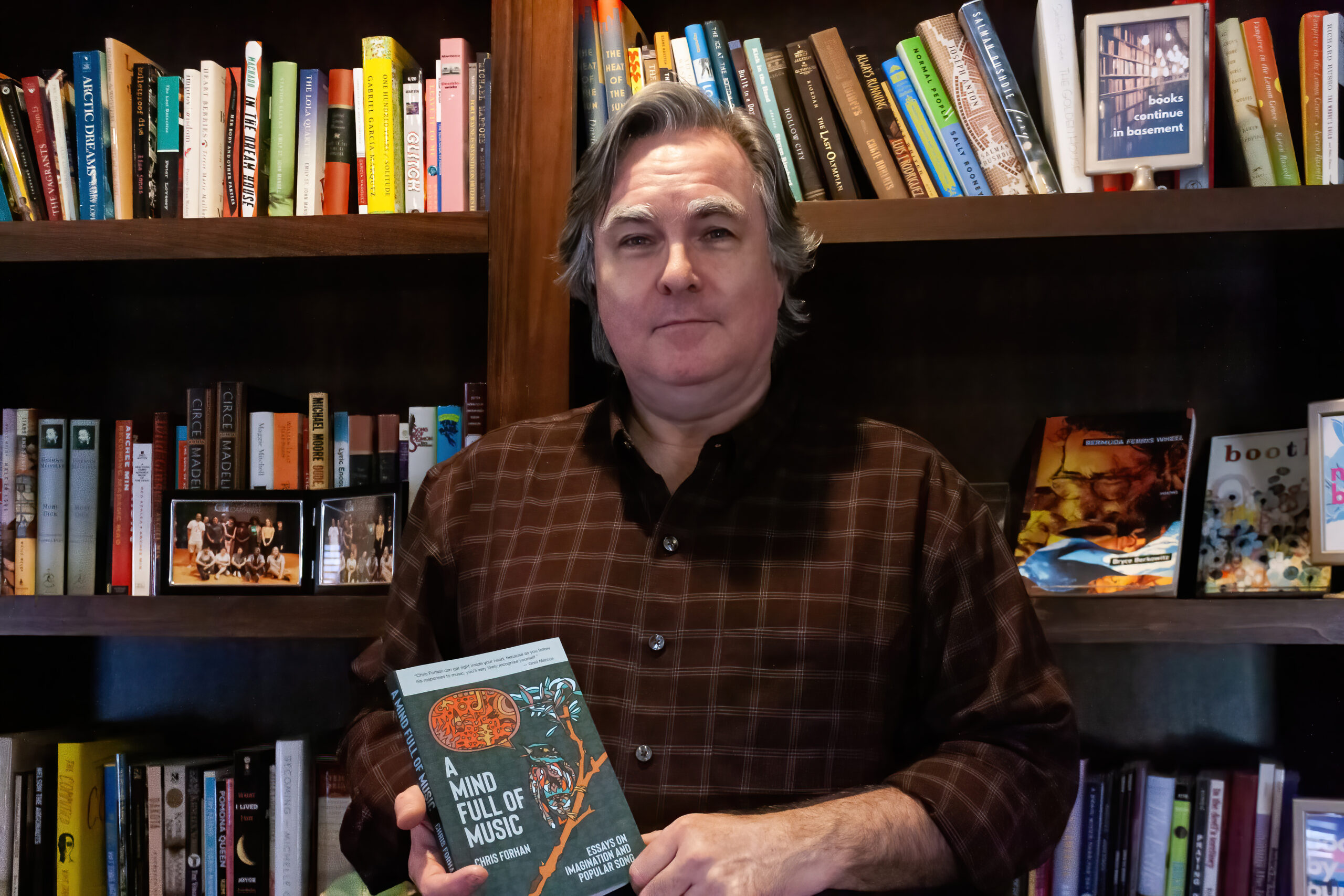

Chris Forhan, a professor in the English department, publishes his second non-fiction book. Photo by Katerina Anderson.

MASON KUPIAINEN | STAFF REPORTER | mkupiainen@butler.edu

Members of the Butler community are achieving extraordinary things, both on and off campus. From first-years to alumni to administrators and back, each Bulldog has a story to tell. Read on to discover the next of our Bulldogs of Butler through a Q&A-style interview.

Chris Forhan, a professor in the English department, has taught poetry at Butler since 2007 and hopes to share writing advice with prospective students. Being a poet himself, he has published five poetry collections as well as two non-fiction books. In his second non-fiction book, “A Mind Full of Music: Essays on Imagination and Popular Songs,” Forhan explores the ways our minds respond to music. Forhan discusses how he fell into writing, his writing process and the inspirations in his personal life.

THE BUTLER COLLEGIAN: What inspired you to get into writing?

CHRIS FORHAN: I think of myself mainly as a poet, and I started writing poems when I was maybe 11 or 12. I suppose what I discovered was poems are the only place I could go to truly be myself, to truly discover and express what I really thought and what I really experienced. So, poetry has always been a kind of solace for me.

I write non-fiction as well. I wrote a memoir, and I have this new book, but other kinds of writing are very satisfying because they allow me to explore a subject and communicate my ideas about a subject. Poetry is the place where I can really go deep into my unconscious and my emotional life to find some form that expresses that. It’s what other people find in religion; I find in poetry as close to the kind of truth as I can get to.

TBC: What do you enjoy most about the writing process?

CF: The publication of the work is always satisfying, but it’s separate from the writing itself, especially with poetry. It’s not the reason to write. The most satisfying part of the process is when I’m right in the midst of writing something, that it’s not [just a] blank page, which can be dreadful. When I feel I’m on the scent of a poem, and I’m just manipulating the language, trying to get it to tell me what it wants me to do with it. [Comparing it to playing chess], you’re right in the middle of this complicated chess match, and you’re just mentally absorbed by it. It’s this kind of an alternate reality, and you’re thinking of all these implications of all the little moves. It’s the same thing when you’re in the middle of writing a poem. It’s mentally challenging and stimulating and satisfying.

TBC: Do you have a specific set writing process that you do?

CF: It depends on what’s going on in my life. I wish I were one of those diligent writers who always wrote from 6 in the morning to 8 in the morning, but I’m not that. I’m either too lazy or too disorganized, or just too busy to be able to do that. When the writing is going well, it means I am setting aside time for it. If we’re talking about poetry, my process is simply to be there for the poem that might happen, which means I’ve got my notebook, and I’m just jotting down words. I probably have a stack of books I’m dipping into to try to kind of get into that poetry [mindset]. If it’s a prose book, I’ll try to go to the laptop every morning at 9 o’clock, and I’ll write for three or four hours. Just whatever happens, happens.

I remember writing the memoir, and I would come to my office in Jordan every day. I put paper over the window so nobody knew I was in there. I’d drop the kids off at school, and then be there in my office for six hours and then go pick up the kids from school. Whatever I could accomplish in those six hours, I accomplished, and I might write 2000 words, or I might write 200, but I get something done.

TBC: Who has inspired you the most? Is it someone in your own personal life? Or maybe another writer?

CF: It’s always hard to say because I like so many writers. It’s hard to tell the difference between my loving them and my being influenced by them. I would say, as a lot of writers have had, I had a great high school teacher, Mrs. Myers, who was maybe the first teacher I encountered who truly took good books seriously. [She] respected them and recognized the complicated nature and took writing – my writing, seriously.

Others I’ll mention [include] my older brother Kevin, who was writing before I was, and was writing poems and showed me that it was possible to do that – to be someone who wrote poems and took them absolutely seriously. Then one of my first teachers, Charles Simic, was a teacher of mine in graduate school, and he was a great poet. [He was] U.S. Poet Laureate for a year. He would say things like, “You want to write poems that will break people’s hearts, make them want to jump off buildings and join monastic orders.” I thought, “Yeah, that’s pretty good. I do want to do that.”

TBC: Since you teach and write poetry, what inspired you to write a book about music?

CF: I’ve been writing poems since I was quite young. I’ve loved songs since I was quite young, as most of us do. Before I was writing poems, I was actually writing songs when I was 10 and 11. I had a guitar, but I knew only a few chords, and I was lazy. I wasn’t compelled to train myself as a musician, and I certainly couldn’t sing, so I stopped writing songs, but I still had the words that I was writing. I realized these are probably poems. I don’t know why, but in the last few years, I thought if there’s one thing I’d like to explore in prose that I haven’t yet, it’s what music does to one’s mind and what it’s like to just have music in your head because I’ve had music in my head my whole life. I realized, if I could be a musician I would abandon poetry immediately, I have no problem. I admire musicians, [and] I admire really good songwriters. Songs are in my head so much that I find myself talking about and thinking about music quite a bit. I figured, why not try to write about music in a way that attempts to capture just what it feels like to have music affect your imagination and your feelings? I was inspired by just the fact that this has been a subject central to me for as long as I can remember. I thought, “I don’t think I’ve ever really read a book that tries to articulate what I’m trying to articulate in this book.”

TBC: How long did it take you to write the book?

CF: I started it in 2017, and the final edits were done just before it was published last year. Five years total, from the first inkling to the last edits.

TBC: How would you describe the book in a brief overview?

CF: I think of it as a kind of lyric meditation. It’s not a big, fully formed argument of a theory. It’s an exploration in little chapters of what it feels like to have songs affect your mind. It’s a celebration of music’s effect on your mind, but it’s also an inquiry into it. Why is it that some songs are haunting, and what does it mean to be haunted by a song? How does that affect the way you proceed with your life and the way you perceive things?

TBC: Do you think that there’s an overlap between poetry and music?

CF: Yeah, I think I think there’s definitely an overlap. Somebody somewhere said something like that about music. Songs and poems share DNA, but they are different things. I quote Walter Pater, the 19th-century writer, in this book. He said, “All the arts aspire to the condition of music.” In other words, music is a superior art. Every other art would love to be able to be music. I kind of agree with that. One beautiful paradox of poetry is that the material of poetry is language. The desire of a poem is to say with this language what language cannot say. To say the unsayable.

TBC: How do you think writing poetry is different from other forms of writing?

CF: Poetry is just a really difficult art; it’s mysterious. I think it is possible to teach people ways to understand poetry and teach people ways to approach the writing of a poem that might help them write a poem. I teach that, so I better believe it. One thing I’ll say is, I think that when people have trouble writing poems, often it’s because they’re [not approaching it] from the right angle. Again, they may be thinking the “left” or “right” in a particular form, or “I have to decide what my subject is, and then find words for that,” which is often the way we write. We write an essay, we decide on our subject, and we ask ourselves, “What do we think about this subject?”, and then we write the essay expressing that idea. That’s not how poems work; poets discover over and over again that the writing of the poem is an act of discovery.

It’s in the way an abstract painter puts paint on a canvas and lets the way the paint is operating on the canvas, telling him what to do next. You have this relationship to your canvas, and it speaks to you, and then you do something to it. Then you’re looking at it, [and] you realize, “Oh, I’ve just put some red there. I think I need some orange over here.” It’s the same way often with poems. You write a line that makes you think, “Oh, I need to do this other thing in the next line,” [even though] you might not have any idea what the poems are about. You’re just kind of working your way toward that understanding and letting the language help you get there.

TBC: Do you have any advice for students who are aspiring writers?

CF: I will give the advice everyone always gives. Read, read, read. That’s the advice. Read everything you can get your hands on. Ideally, the good stuff. When I was 10 and 11, my main reading material was “Sports Illustrated” magazine, which came to my house every week, and I read it front to back every week, even the lacrosse stories. I realized, looking back, that [it] actually taught me a lot about how to write a sentence and how to construct an article and essay, how to tell the story. It doesn’t matter what you read, even if it’s the back of a cereal box. If you can read Dostoyevsky, all the better, but just read, read, read. Slowly with attention, not in the skimming way that we’re so used to these days.

TBC: A lot of writers talk about finding their voice. Do you have any advice for students trying to find theirs? And how to find your voice? Or maybe how you found yours?

CF: I don’t know that I found mine. Perhaps I have, [but] I wouldn’t worry about it. I’ve never worried about it. I don’t even know what that means to have your voice. I just think, does the thing I’m writing work? Is it authentic? Does it sound as if I’ve really created something that sings, that has music to it, that has force, that has emotional power? Does it sound true? If so, I’m satisfied.

TBC: Are you currently working on a new project?

CF: I’m just trying to write poems, but I don’t have any particular big project in mind now. I wrote a pretty big prose book a few years ago, [“My Father Before Me: A Memoir”]. That was a giant, unwieldy project. It was very rewarding, but I never thought I’d write a book of prose. I was always writing just poems. After I wrote that book, [which] was published in 2016, I thought “I don’t think I ever want to do that again.” Then this idea [for “A Mind Full of Music”] came to my head, and this was a little happier and easier to handle. It wasn’t excavating my difficult childhood; it was just having fun thinking about music, but I don’t have anything like that in my mind right now. Right now I’m thinking I’ll never do that again, but then, who knows?

“A Mind Full of Music: Essays on Imagination and Popular Songs” is available to purchase through all major book retailers.