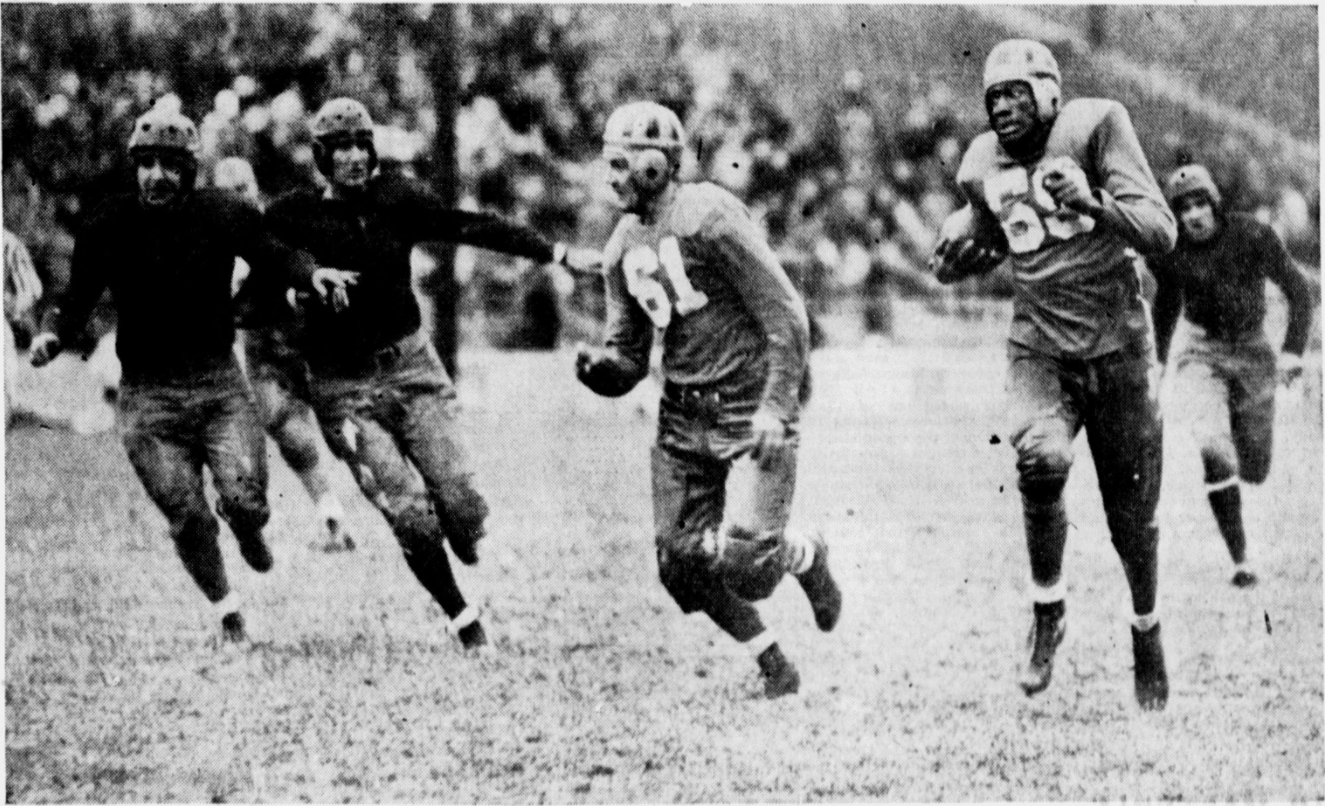

Thomas Harding rushes for a touchdown against Washington & Jefferson. Harding earned eight athletic letters while at Butler before graduating in 1940. Photo courtesy of IndyStar.

DREW FAVAKEH | CO-SPORTS EDITOR | dfavakeh@butler.edu

When Linda Harding was 13, she read an article that detailed the racism her father faced when he was a star at Butler University in the late 1930s.

On the bus that took the Bulldog team to the games, her dad, Thomas Harding had to hide — under blankets, beneath the seats, in the back of the bus — so onlookers couldn’t see the only Black player on the team.

Linda was surprised. So, she asked him about it.

“He said, ‘Well you know, honey, things have become so much better, but we still have a long way to go,”’ Linda remembers her dad saying.

Such a story is largely not unique to what many Black athletes endured during those times. But while the likes of Jackie Robinson, Jesse Owens and Muhammad Ali received praise, if not recognition, after the fact, Tom Harding’s story remains mostly obscure.

Like Robinson, Harding excelled in football, baseball and track. He won eight athletic letters, which no Butler athlete before or since has accomplished. His collegiate career was, well, the stuff of legends.

“In one game, Harding blasted a pitch that sailed only 15 feet short of the fence gate in a deep center at Butler — 450 feet away,” the “Indianapolis Recorder” wrote. “Only Gil Hodges, a familiar baseball name, ever put one near that spot.”

At 6-foot-2 and 195 pounds, Harding ran the 100-yard dash in 9.7 seconds, making him the state’s fastest runner who happened to be built like an ox.

“An erect young man, with a glad smile, as straight as the Washington Monument, he ran with speed and drive and a high knee action that once broke a tackler’s collarbone in a freshman scrimmage,” the “Indianapolis Recorder” wrote.

When local newspapers wrote about Harding, they almost always included a disclaimer of his race. Common nicknames for Harding from local newspapers included “colored ace,” “fleetfooted colored ace” and “negro flash.”

“After watching Thomas Harding in action, this department would dub him the ‘Brown Bomber of the Bowl.’ They called “Red” Grange the ‘Galloping Ghost of the Gridiron,”’ the “Butler Collegian” wrote in 1938.

But Harding didn’t let the noise affect him.

“My dad always had a positive outlook on everything,” Linda said. “If you’re gonna fall down, you’re gonna get back up again, Linda. He was always like, ‘Don’t let that stop you from reaching your goals. You put your trust in God and He will take you far.”’

Devout faith was instilled in Tom from a young age. His dad died when he was three years old. His mom and two older sisters “raised him in the church,” Linda said.

As a father of six, Tom never pushed his children to play sports. Instead, he stressed the importance of education.

“He was always strong on education,” Linda said. “He would always say, ‘Linda, you need to stress your education because we’re Black and the only way we’re gonna get ahead is through education.’”

The Start: Harding’s high school and college years

Harding graduated from Crispus Attucks, then-Indianapolis’ all-Black high school, in 1935. There, he excelled in baseball, track and especially, football.

“No team to date has succeeded in stopping [Harding],” the “Indianapolis News” article wrote in 1934. “In every game, he has ripped off from seventy to 140 yards. This great ‘Tiger’ man stands six feet, runs the length of the field in fair dash time, and is reported as a coming grid star equal to any in local high school circles, with possibilities for development when he reaches college circles.”

That same newspaper clipping reported Harding considering enrolling in Purdue University, Indiana University or Butler University. Instead, Harding chose to attend Morehouse College, an all-Black school in Atlanta.

Thomas Harding Jr., who goes by Tommy, said in a phone call he wasn’t privy to why “daddy went to Morehouse initially,” but he knows his mom got “real, real sick, so he had to come back home.”

“Leaving Morehouse and coming to Butler was a godsend for him,” Tommy Harding said. “It helped make him the man who he was.”

Butler’s assistant football coach and lead recruiter at the time, Frank Hedden, mostly referred to as “Pop” because of his bald head and fatherly presence, heard Harding was unhappy at Morehouse and contacted him.

“He assured him that, like many other players, he could earn money from jobs at Butler to cover the school’s tuition and book costs,” Howard Caldwell wrote in “Tony Hinkle: Coach for All Seasons.” “Butler offered no athletic scholarships; needy team members earned their way through such jobs as maintenance of the fieldhouse and waiting tables.”

Tommy also said Alonzo Watford, Butler football star in the 1920s and Crispus Attucks Athletic Director, helped his dad transfer to Butler.

Harding throws a stiff arm to an out-of-frame picture during a game at Crispus Attucks. Photo by IndyStar.

“Watford was a mentor to several of them [Crispus Attucks graduates],” Tommy Harding said. “They had a bond that…I don’t know…I don’t think people have that today. Coming from where they came from and sharing what they shared made [their bond] what it was. As a result of that, [the Crispus Attucks graduates] were responsible for breaking barriers.”

Harding transferred from Morehouse to Butler after his first semester freshman year. As soon as he arrived in Indianapolis, Harding had to prove himself.

“The first scrimmage we had, with the varsity against the freshman, including Tom, the varsity roughed him up,” Tony Hinkle, Butler football head coach at the time, remembered years later, in 1961.

But Harding didn’t back down.

“Afterwards, I heard the varsity talking about him — how they’d done everything to him and he didn’t whimper,” Hinkle said.

As a sophomore in 1937, Harding came off-the-bench for the first four games, but by the fifth game, he was starting at left-halfback. By 1938, Harding broke out, becoming one of the best running backs in the country. He was so dominant that opposing teams went to extreme lengths to sideline him.

Resiliency: George Washington game

A few hours before his team was scheduled to leave by train to Washington D.C. for a game against George Washington University midway through Harding’s junior season in 1938, Tony Hinkle received a telegram.

George Washington would not play Butler if Tom Harding suited up.

Upset, Hinkle told Harding he would cancel the game if he wanted him to. But Harding objected.

“Harding said he thought the teams should play and that maybe someone would note the irony: a university in the nation’s capital was rejecting him because of the color of his skin,” Howard Caldwell wrote in his book, “Tony Hinkle: Coach for All Seasons.”

“When we play ‘em again, we’ll beat ‘em,” Linda said her dad told Hinkle. “I can promise you that.”

On that trip, Harding was also not allowed basic amenities, Channa Beth Butchner, remembers her dad, Channing Vosloh, Harding’s Butler football teammate, saying.

“They took the train from Indianapolis and Tom Harding could not be in the same train car with them,” Butchner said. “He couldn’t stay in the same hotel with them. He couldn’t eat with them. He had to be in totally separate facilities.”

The day before the game, most of the Bulldogs took part in a sight-seeing tour of D.C. — including the White House, the department of commerce, and the FBI — without Harding.

Even though he was barred from playing, Harding, wearing street clothes, still attended. Watching his team lose 26-0, Harding was berated with “abusive language and a chorus of boos,” Caldwell wrote, which he ignored.

“He just held his peace, he just collected his thoughts,” Tommy Harding said. “He said when they would come to Indianapolis, he was going to remember all of this. And once he decided he was going to do something, he was going to do it, come hell or high water.”

The next year, Butler had a rematch against George Washington. The Bulldogs were undefeated going into the game again, but this time, they had home-field advantage. With Harding available, he dominated, scoring two touchdowns, running 72 yards for one, passing for another, and kicking a conversion. It was a typical performance for Harding, who finished second in the country in individual points scored.

“Harding was a demon, making tackles all over the field and hurling himself onward in an afternoon of retribution,” the “Indianapolis Recorder” wrote.

But even when Harding was allowed to play, the Colonials didn’t make things easy.

“The next year, George Washington played here and the Colonials were throwing a knuckle where a hand might have done the job,” the “Indianapolis Star” wrote. “And always it was a grinning Harding who would bounce out a tackle ready to try again.”

“After the victory over George Washington in football, the Butler player who was awarded the game ball turned it over instead to Tom, saying, “This belongs to you, not to me,”’ the “Indianapolis Recorder” wrote.

Such a display of resiliency wasn’t unusual for Harding, Bob Collins, then an “Indianapolis Star” columnist, wrote in 1998.

“I remember, as a youth, watching tacklers slam Harding into a wall that was a good 15 yards off the playing field. He had to be hurting. Bad. But he bounced up with a smile and continued,” Collins wrote.

Years later, his daughter, Linda Harding, asked him: Did sitting out that first game against George Washington bother him?

“Well, I was hurt,” Linda remembers her dad saying. “But I knew I was gonna beat them. I asked, ‘You knew you were gonna beat them?’ He said, ‘I did know. We lost the first game because I wasn’t playing.’”

Harding breaks a tackle against George Washington in the Butler Bowl as a senior. Photo by IndyStar.

Father Figure: Coach Hinkle

In the chateau room of the old Claypool Hotel in Indianapolis, Tony Hinkle took to the podium. It was 1961.

Some 375 people listened to Hinkle call Harding “the best player Butler ever had.”

“Maybe, I’m prejudiced,” Hinkle said. “Because we fought so many things together. We went through the beginnings of the colored athlete playing college sports. At restaurants, I had to tell them we had a colored boy on the team. He had to eat by himself. He took it all so well.”

The feeling between Harding and Hinkle was mutual.

“Under his leadership, I was able to accomplish much,” Harding, then a retired Indianapolis Public School teacher, said as an honorary pallbearer at Hinkle’s funeral in 1992.

“I think it was a very good relationship because my dad admired him so much. He was like a father to him,” Linda Harding said.

Revered at Butler: Harding Receives Scholarship

While Harding was largely revered by Butler, the same could not be said for other Black students at the time.

From 1927 through 1948, only 10 Black students were allowed per graduating class at Butler, Sally Childs-Helton, Butler University Special Collections and Rare Books Librarian, wrote in an email.

“That cut down considerably on the number of potential students of color during those years who could play sports,” Childs-Helton said.

But, as an impressive athlete, Harding received special treatment.

Take a ceremony in 1940, days after his college graduation.

As a strong gust of winds blew snowfall through the Butler bowl on a mid-afternoon day in mid-January, Harding was presented with a post-graduate scholarship.

“That the crowd braved the weather is a tribute both to them and to the esteem in which they hold Harding,” the “Indianapolis Recorder” wrote.

The Senate Avenue YMCA, where Harding was working after his graduation, granted Harding a scholarship worth $3,300 for “graduate study at one of the specialized schools of physical education and public recreation,” the “Indianapolis Star” article wrote.

Walking onto the snowy field, Harding was serenaded by the Crispus Attucks choir.

As the music faded, a presiding officer took to the podium to provide an introduction to the special occasion.

“Only once in a century does the time come when the spirit of democracy actually lives,” the presiding officer said. “That spirit lived Sunday and it lived because Tom Harding played football and other sports with his person in the game but never so far to the front that people mistook his game for personal glorification.”

Hinkle was next to take to the podium.

“[Tom is a] gentleman at all times, smart, jovial, even-tempered, and with an unlimited ability in many lines other than athletics,” Hinkle said. “[He built] inter-racial goodwill in the community — a case where genuine merit brings its own reward.”

Harding’s former football teammates then took to the podium.

“They came to attest the truth of the statement that Tom Harding is the ‘captain who throughout his career, has sacrificed his personal glory and has shown an undaunted spirit of unselfishness in all his play,’” the “Indianapolis Recorder” wrote.

Dr. William Rothenburger, the pastor of the Third Christian Church, also spoke.

“Universal elements in men’ advanced the thought that race, color, creed, or religion cannot bound personalities or their worth as personalities,” Rothenburger said.

Lastly, Daniel Robinson, President of Butler University from 1939 through 1942, presented Harding with the scholarship.

“[Robinson] called attention to the fact that Tom the young man had achieved much and Butler University was proud of that fact,” the “Indianapolis Recorder” wrote. “He intimated that he hoped many more would continue to achieve.”

But if Harding was mostly revered during his collegiate career, he was not so fortunate in the professional ranks.

The 1936 Butler Bulldogs with Harding pictured [top left]. Photo by IndyStar.

Six years before Jackie Robinson donned 42 in baby blue, it was Tom Harding who was nearly chosen to break the MLB color barrier.

“He was pretty fast and I was pretty fast, too,” Harding told Dick Mittman, former “Indianapolis Star” Reporter, about Robinson, in 1998. “I thought he was a great player — the greatest — breaking in in that era. If I’d had the chance I would have played. In my estimation, I could have made it.”

Ruth, Harding’s wife of 60 years, agreed.

“That’s the truth,” Ruth said in the 1998 “Indianapolis Star” article. “It was a choice between Jackie and Tom.”

Herb Schowmeyer, a member of the Butler basketball team when Harding was at the school, remembered Brooklyn Dodgers scouts watching Harding practice.

“He’s the man they would have taken if Robinson hadn’t been chosen,” Schowmeyer said in the 1998 “Indianapolis Star” article.

But race proved the ultimate equalizer.

Jim Haas, a student at Butler at the same time as Harding, said in the 1998 “Indianapolis Star” article that he remembers “scouts coming out and saying they wished he was white.”

“Scouting him once, Clarence ‘Pants’ Rowland, president of the Pacific Coast League, voiced a lament that the time wasn’t ripe,” the “Indianapolis Recorder” wrote.

One organization did offer to sign Harding — so long as he moved to Cuba first. In an odd twist of unwritten rules, Latino people were allowed to play, but not African-Americans.

“They could get better acceptance by bringing him into their program as a Cuban,” Caldwell wrote in Tony Hinkle: Coach for All Seasons. “Harding said no thanks.”

Finding a Way: A Semi-Pro Career

Barred from playing at the top professional level in every sport, Harding was relegated to other athletic outlets.

Harding played in the Negro League Baseball League, for the Indianapolis Crawfords in 1940 and an unknown team in New Orleans in 1945, according to The Negro Leagues Book, Volume 2.

“Had an opportunity arisen, I think daddy would have pursued baseball,” Tommy Harding said. “When those barnstormers like Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige and Oscar Charleston used to come here, he would do quite well. We used to walk to those games. It was excitement, unparalleled. Daddy could hit a baseball a country-mile. Centerfield at Victory Field used to be 500 feet out there, and man, it was nothing for him to one over there.”

Harding was equally dominant in professional football. But since Black players wouldn’t break into the NFL until 1947, Harding played semi-pro football with the Indianapolis Young Democrats in 1940, the Indianapolis ABCs in 1941, and the Indianapolis Pal Club Gridders in 1944.

As the “main cog in an offensive machine,” according to a 1940 “Indianapolis Star” article, Harding led the Indianapolis Young Democrats to a 5-1 record, with dominating wins 56-0 over the Muncie Flyers and 40-7 over the Dayton Fliers.

“Harding, former Butler flash, romped for two touchdowns, going 75 yards in the first period and 78 in the second. He also accounted for two conversions,” an “Indianapolis Star” article read.

It would be no surprise that, when Harding took up boxing, he was dominant in the ring, too. After winning back-to-back heavyweight crowns in the annual Marion County Amateur Boxing Championships in 1938 and 1939, Harding won the third annual Golden Gloves tournament in 1940, scoring a knockdown in the third round.

“A crowd of approximately 3,000 was on hand to witness the wild-swinging parade of future Jack Dempseys and Joe Louises,” the “Indianapolis Star” wrote in a 1940 article. “Among the victors was Tom Harding, Negro Football star of Butler…The collegian won the decision and looked like a fairly good prospect in the class. He has speed and good footwork as well as a quick left.”

With the United States embroiled in World War II, Harding enlisted as an army corps serviceman, and he served in 1943 before being honorably discharged.

After he returned from war, he signed with the Indianapolis Lincolns, a semi-pro baseball team, in 1947.

Shortly thereafter, he joined the Senate Avenue YMCA, which was segregated, as the athletic director, marking the end of a short-lived professional athletic career that would have been even more decorated had he been born just half a decade earlier.

Harding poses with three teammates for the Indianapolis Young Democrats, a semi-pro football team in the 1940s.

Passing It On: Teaching

After working at the YMCA, Harding worked as a P.E. teacher, baseball and football assistant coach, and senior counselor at Shortridge High School, until he retired in 1984.

While Harding enjoyed playing sports, teaching was his true passion.

“Seeing a student reach personal satisfaction, growth, and show some type of motivation are the rewards one receives in this profession,” Harding said after he retired from Shortridge High School in 1984.

Oftentimes, Harding hosted local Black athletes — such as future Oscar Robertson, then a Crispus Attucks star guard and future NBA hall-of-famer — at his house for dinners.

“He took the time to develop those kids who were coming along who would have that pinnacle of success that he didn’t have on the national scale,” Tommy Harding said.

Black students and athletes at Shortridge High School, which consisted of mostly white students, often confided in Harding, Ray Satterfield, a 1960 Shortridge graduate, said.

“It was nice to know that someone of the same ilk, the same color was there for us,” Satterfield said. “There was some comfort with Coach Harding being Black and him being there for me. He was a big man, all muscles, but he was a gentle giant. He was a remarkable athlete — I once saw him drop-kick a football 70 yards — but to me, his humanity exceeded his athletic prowess.”

Fletcher “Flash” Wylie, a student and former player of Harding’s, remembers walking into Mr. Harding’s office and opened up about another student acting racist towards him. After listening to Wylie vent, Harding fed him advice.

Wylie, who is Black, called Harding a “father figure.”

“He said that he recognized that nothing is perfect, that racial discrimination exists, and he was aware of life in that respect was unfair,” Wylie said. “But he wanted me to utilize all the resources I had at my hand to defeat racism.”

Harding teaches at Shortridge High School in 1956. Photo by IndyStar.

Special thanks to Sally Wirthwein, Butler Historian, and the Harding family, who helped tremendously to form this story.