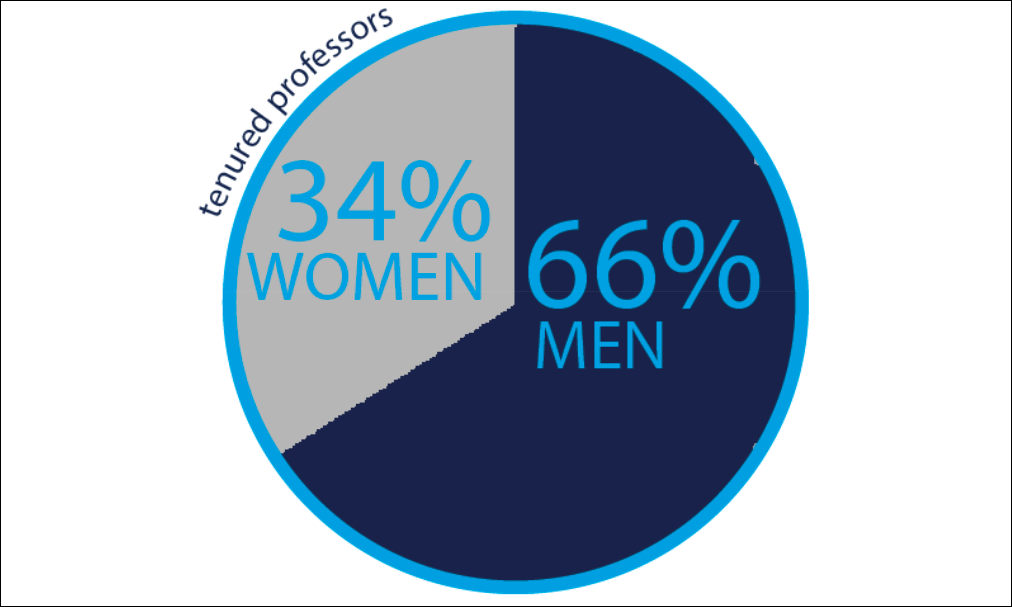

According to national statistics by catalyst.org, only 34% of tenured professors are women. Graphic by Trinidy Charles.

JOE KRISKO | ASSISTANT NEWS EDITOR | jkrisko@butler.edu

Following an investigation by the Department of Labor into pay discrimination, Princeton University has agreed to pay over $900,000 in back-pay to female professors at the institution. Just a week later, data released by the US Census Bureau revealed that no progress has been made in closing the wage gap between women and men. At Butler, several women who have risen to the role of full professor shared their experience on how Butler has evolved in the area of gender equality over the years.

When Hilene Flanzbaum, a professor of English, arrived at Butler almost 30 years ago, she said Butler and the Indianapolis community were very different compared to how they are today. She recalled one instance from her earlier days at Butler when she went to submit a grant application on campus.

The woman in the office that Flanzbaum gave the application to kept asking her who the grant was for, even after Flanzbaum had said the application was hers. After a back-and-forth conversation and a series of misunderstandings, Flanzbaum realized that the woman had just assumed she was a secretary submitting the application for her boss.

At that time, it was uncommon for women to be professors at all, let alone rise to the rank of full professor.

Kathy Gjerde, a professor of economics at Butler, has been at the university for over 20 years. When she arrived at the College of Business in 1997, things were very different. Before she and another professor were promoted to the title of full professor in June of this year, there had only been one woman to ever hold the title of full professor in the history of that college. At the time, that professor was also the only female professor to ever be considered for full professor in the College of Business.

“I think that’s the issue,” Gjerde said. “It’s not that people are being denied, it’s that people aren’t going up.”

At Butler, there are typically two basic career paths. Faculty can either start out on the tenure or non-tenure tracks. Those who are not going for tenure normally have titles like lecturer or adjunct. However, the faculty that start out on the tenure track get the title of assistant professor.

After about six years, assistant professors go up for tenure, a months-long process which evaluates candidates based on their time at the university, service and research. If a professor successfully navigates this process and secures tenure, they will also receive a pay raise and be promoted to the title of associate professor. Once professors receive tenure, they can no longer be fired or laid off except for in extreme circumstances.

After these promotions and a few more years at the university, professors are finally eligible to be promoted to full professor.

Gjerde said that in addition to there not being many professors who apply for full professor in her college, there are also not as many women represented in the fields taught in the Lacy School of Business.

Avery George, a junior computer science, psychology and engineering triple major, has noticed this sort of unequal representation in certain fields based on gender. For example, George said he has not had a single computer science class taught by a woman. Simultaneously, all but one of his psychology classes have been taught by female professors.

George said representation among professors could also be important for some students. As a man, George said he could not speak for the effect being taught only by men has on female students. However, he said that as a Black student, seeing Black faculty and staff can be encouraging.

“Not only are they a form of inspiration and a goal to achieve, but they also put forth that effort and… provide assistance [for] students of color if they need it,” George said.

Professor of communication Ann Savage was glad to see Princeton would be giving back-pay to professors, especially considering the size of the school’s endowment.

“It’s about time,” Savage said. “Princeton has plenty of money.”

At Butler, Savage said much of the change surrounding gender equality has been driven by faculty. During her time at the university, a group of professors started a women’s caucus for faculty and another contingent of faculty members started a group called the Collaborative for Critical Inquiry into Race, Gender, Sexuality and Class.

When she started at Butler, Savage noticed that there were not many women represented in the role of full professor, but since then, she has seen a lot of women move up to this position, even if there is still not full equality in the role.

“Once a few women did it and broke the seal, more women went,” Savage said.

Savage said sexism and even racism can be widespread, though they may not always be overt.

“Racism and sexism are everywhere and Butler is not absent of that,” Savage said. “And again, racism and sexism is not people walking around and saying, ‘Oh, I hate women, I don’t want to promote them,’ it’s much more subtle than that.”

For Flanzbaum, the sexism she saw was also structural. She arrived at Butler when she was in her thirties and still wanted to have kids. However, having two kids while also trying to manage the workload necessary to eventually go up for tenure posed challenges.

“When a woman has to stop her tenure clock to have a baby, or even to take maternity leave, that makes her less experienced than her male colleagues; that means she has fewer years in; and that means their salary is automatically going to be less,” Flanzbaum said.