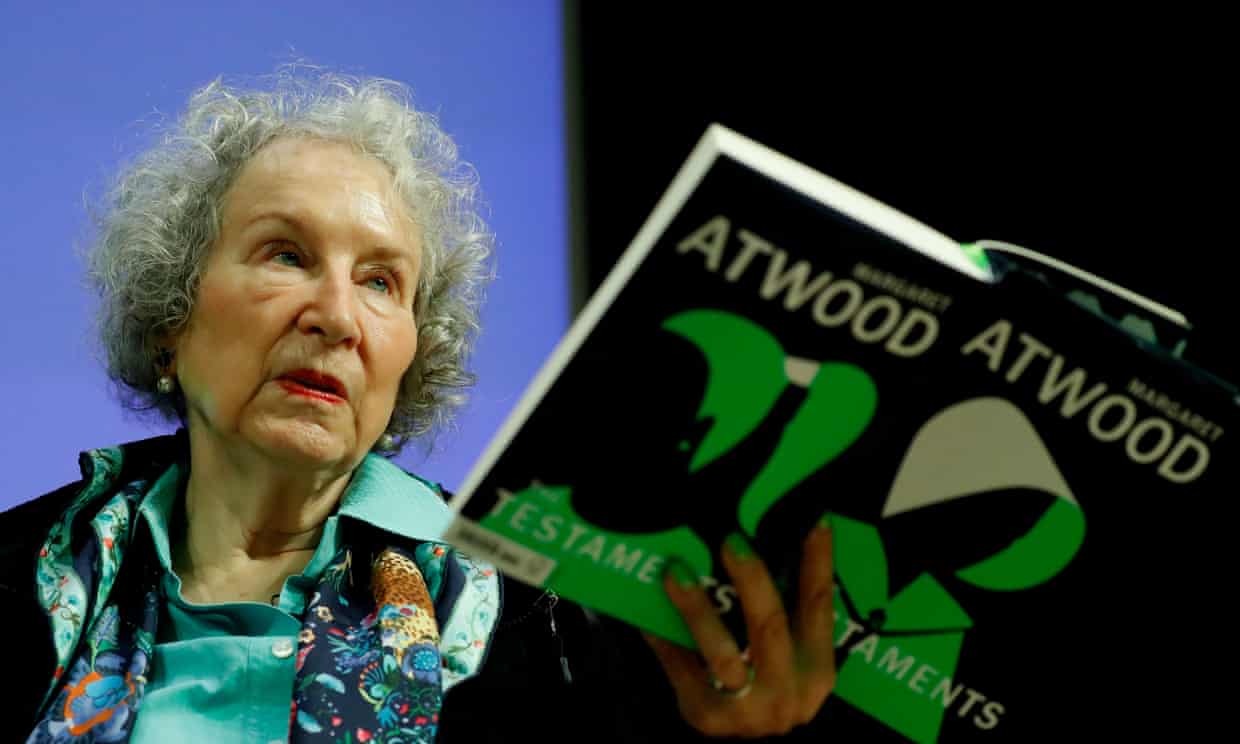

Margaret Atwood releases a sequel to “The Handmaid’s Tale” 34 years after its publication. Photo courtesy of The Guardian.

LYDIA ZIDAN | STAFF REPORTER | lzidan@butler.edu

Having recently read Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” and watched the gut-wrenching finale of the novel’s TV counterpart, I was expecting to again put down her prose, nauseated. Surprisingly and refreshingly, 34 years after its predecessor’s release, Atwood’s “The Testaments” is a testament in itself to the power of the human spirit and the lengths one will go to for survival, detestable or otherwise.

“The Handmaid’s Tale” is a dystopian novel by Atwood, set in a near-future New England, in the totalitarian, theocratic state Gilead, which has overthrown the United States government. The novel focuses on the journey of the “handmaid” Offred, a woman captured by the regime for the purpose of forced reproduction.

That said, many have compared today’s society to what NPR book critic Maureen Corrigan delightfully termed “Gilead-lite.” When asked about where Atwood took inspiration from, she said, “Well, almost everything! The other inspiration is the world we’ve been living in.”

“The Testaments” is set 15 years after the first story and follows the formative experiences of three very different women. Two of the narrators are young, ready and willing to bring down Gilead from the inside out. The other? An unlikely pseudo-protagonist who you all may remember wishing death upon in Atwood’s last installment. You guessed it: Aunt Lydia.

As infuriating as it is, “The Testaments” begins to justify Aunt Lydia’s callous ways, even if only at a primitive level. And although her glory days wreaked enough havoc upon the lives of the Handmaids to earn a statue of her likeness as a small token of appreciation for her many accomplishments, I felt a twang of guilty empathy and even started to root for Aunt Lydia. This was especially true when an expected but nonetheless dazzling plot twist was unveiled. To survive, she had to assimilate to Gilead’s regime, yet mentally remained objective — a great feat of strength regardless of the atrocities she committed and an attestation to our resilience as a species.

Our other narrators drive the plot into motion, leaving behind the stagnant, depressing and frankly dead nature of “The Handmaid’s Tale” and propelling readers to think of a future without Gilead. Daisy, a stubborn teenage girl from Canada with an interest in joining the resistance, and Agnes, the daughter whom Offred risked life and limb for, both fight against the patriarchal and misogynistic themes that run rampant in both “The Handmaid’s Tale” and “The Testaments.”

For a woman verging on 80 years old, Atwood captures the teenage voice surprisingly well, at moments leaving me chuckling unexpectedly. Again, the plot twists pertaining to the girls sometimes verge on the anticipated, yet seems to be at no detriment to the overall message Atwood is trying to convey. This book is nothing like “The Handmaid’s Tale.” It can not capture the same silent defeat, and maybe that is for the best.

In Aunt Lydia’s final journal entry, we are reminded that eventually “nail polish will have returned” and Gilead will be nothing but “pages in a fragile treasure box.” I would not call “The Testaments” a feel-good novel, but Atwood suggests the beginnings of hope and reminds us that the kids are gonna be alright.

Thank you, Lydia Z, for this perceptive glimpse into Atwood’s new book. I think we humans go through cycles of sorts, both in fiction and in actual life, both individually and as societies; and despair usually at some point yields to hope. We’ve seen the other side of that curve too, of course, but even in our deepest valleys of despair, hope beckons us. I think you and your peers — people like Greta Thunberg — are on the upward slope of the curve. Thank you for helping lead the way!