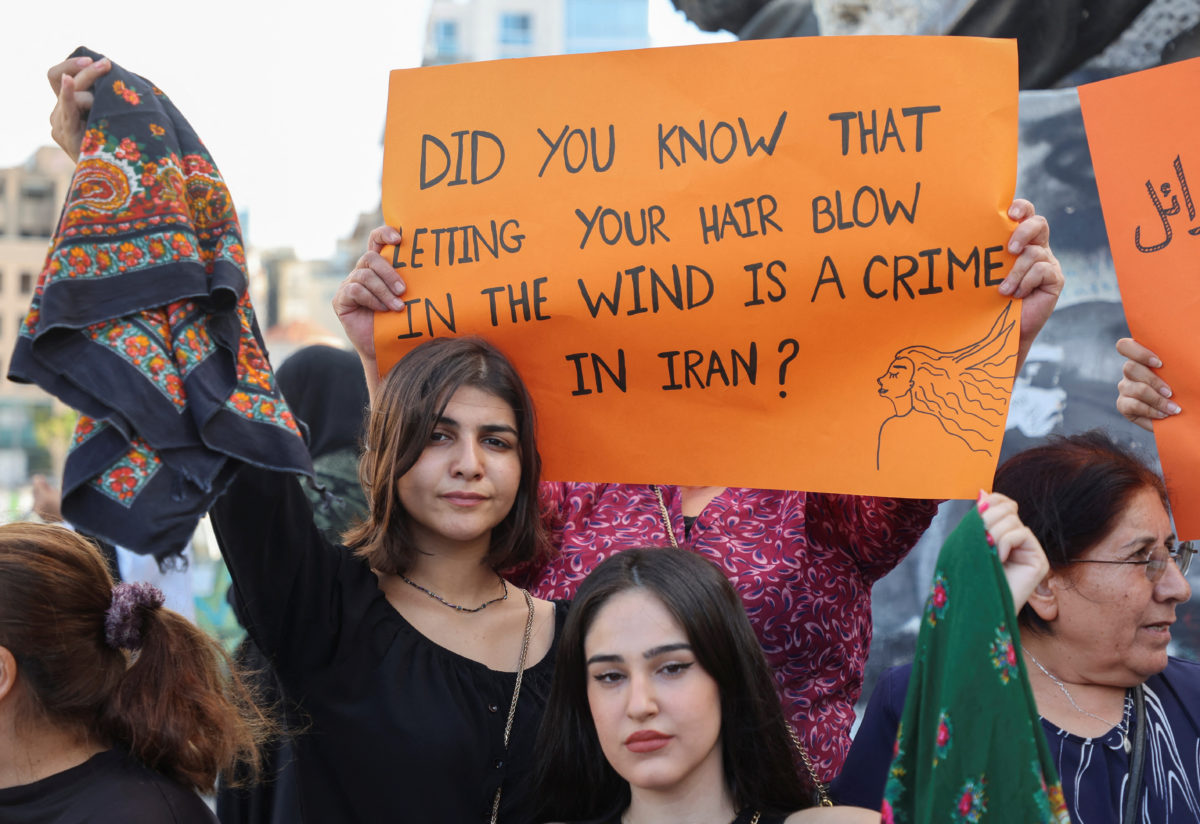

Mahsa Amini’s death has sparked protests throughout Iran. Photo courtesy of The Guardian.

SADIA KHATRI | OPINION COLUMNIST | sskhatri@butler.edu

Content warning: This article contains references and depictions of police violence and brutality.

On Sept. 13, 2022, Mahsa Amini was held captive by Iran’s morality police. On Sept. 16, 2022, Amini was found dead while under police holding.

Mahsa Amini was a 22-year-old woman from the northwestern Kurdistan Province in Iran who was visiting Tehran, Iran with her family. On Sept. 13, she was arrested by the police for dressing immodestly. It is believed that Amini was arrested for violating the headscarf — also known as hijab — law that Iran has in place. Three days following her arrest, Amini was dead under police custody.

Officially, Amini died in a hospital in Tehran due to a heart attack, although Amini’s family refutes this belief. Her family has stated that they saw Amini get brutally beaten in the police car while she was driven away to the police detention center. There are reports that show that Amini’s death may have been caused by a fractured skull caused by a heavy blow to the head. Amini’s family was unable to see the entirety of her dead body, but her father saw her foot and said that it was heavily bruised. Amini’s funeral took place on Sept. 17, and since then, protests have broken out throughout Iran. The belief that Amini’s death is rooted in her getting beaten by the police shows the unfortunate extent to which the police have power in Iran. Not dressing “properly” should not be a death sentence for any woman.

Iran has laws in place to ensure the modesty of both men and women, but women are disproportionately impacted by these laws. After the 1979 Islamic revolution, laws on women’s modesty entered the realm of Iranian government and politics. On March 7, 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini instituted the law that hijab would be mandatory for all women, regardless of their religion or nationality. These laws claim to promote modesty and a sentiment of piety among the population, but they have most definitely not done this. Strict mandated dress codes lead to animosity and indignation and will never serve the purpose they claim to support. They will never lead to people being more religious or spiritual, for that is a personal journey that force and violence will never be able to foster.

Anthropology professor Dr. Sholeh Shahrokhi is from Iran and spoke about the multitude of factors that have impacted Iran as an Islamic state.

“In 1979 there was a revolution … followed by a major referendum,” Shahrokhi said. “And that referendum resulted [in] a political system unlike any other at that point: an Islamic republic. Nobody really at that point knew what that meant or what [that] was going to be. But it was a reaction to the political status quo and the frustration people felt in Iran … and the need to have a more democratic political system.”

However, there are not many explicit details describing what does or does not qualify as properly modest clothing. Women who are not dressed properly — according to the arbitrary interpretation of modesty laws by police — are subject to police detainment as well as other, harsher forms of punishment. It is absurd that women face consequences for something that is not even outlined in these laws. There is no rhyme or reason as to why or when a woman may be punished. The morality police harshly condemn women for their lack of modesty, and Shahrokhi provided some additional insight on this as well.

“[Out of the revolution], in the 80s [there] came a volunteer-based militia group that was immediately sanctified and organized as an official branch of the government,” Shahrokhi said. “The ‘modesty guardians,’ if you will, they began to screen the streets … But as the political tensions in Iran during the war … intensified, the role of these ‘scanners’ across the country became more militarized … So what we see today, which roughly translates to ‘morality police,’ they are policing … the conduct of people … Nine out of 10 times you could be perfectly acceptable by the morality police, and then there’s one time that they pick you out of the crowd.”

In Iran, women are calling for an end to the forced hijab laws. Many Iranian women have begun burning their headscarves and cutting their hair publicly as a symbol of their resistance against the Iranian regime and in support of Amini. These protests show the extent of support that people around the world, and especially people in Iran, have towards supporting women in their ability to choose to dress the way they please. This support is very important and shows the world — and more importantly, the Iranian regime — that people do not support forced dress codes and that women should be able to dress how they please. This can be succinctly expressed through the common protest slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom”.

The account for Iran Human Rights recently tweeted that security at Sharif University in Tehran have attacked protesters and that shooting was heard. The protests are escalating as people continue to call for an end to the Iranian regime and its oppressive politics.

Some Muslim women choose to wear the hijab, while some do not. Both choices are valid, but Islamically, wearing the headscarf is mandatory for women. However, a person should not be forced to do anything. Free will is an important aspect of Islamic beliefs, and individuals should always be able to make decisions for themselves.

Yossra Daiya, a sophomore political science and psychology combined major, is — like me — a Muslim woman who chooses to wear the hijab. Daiya emphasized the importance of wearing the headscarf in her daily life, but explained that the Islamic concept of free will is an important idea to understand with respect to wearing the hijab.

“[Practicing Islam] comes of your free will,” she said. “[In Islam], women are given the rights to be able to choose whether or not [they want] to wear hijab … Women are being forced to practice the hijab in Iran, and anything that is forced is oppressive.”

To reiterate Daiya’s point, it is un-Islamic to force people to do things out of their free will. Not understanding this principle has harsh consequences, and has the potential to contribute to Islamophobia and oppressive legislation. Legislatively mandated religion has the potential to take away the individual liberties of people, and from an Islamically uninformed perspective, this causes Islamophobic sentiment to proliferate; people begin viewing un-Islamic representations of Islam as definitively Islamic.

Dr. Nermeen Mouftah, associate professor of religious studies, spoke about the complexity of free will and personal agency in Islam.

“I think the emphasis on this question of choice is something that’s modern, whether that’s Islamic or not Islamic,” Mouftah said, “Our modern sensibilities … place a lot of emphasis on human agency … That’s not how Islamic scholars have approached the issue [historically] … I also think it’s more complex than this question of choice. And it’s even more complex than this question of what the law is because we’re shaped by things beyond the law.”

Mouftah explained that although free will is an important aspect of Islamic beliefs, Islamic societies and scholars have often focused on how to implement practices to maximize spiritual benefit for Muslims. For the ideal Islamic society, spirituality and piety would be important factors. Some Muslims may make choices solely for the sake of God.

“I think it’s really difficult for secular society to appreciate the idea that … my agency is actually a secondary issue,” Mouftah said.

Where the secular Western world emphasizes the importance of individualism, Islamic societies and practices have often been more focused on collectivism and community. It is critical to not view this issue through a Eurocentric, white feminist lens, considering the difference between collectivism and individualism is one that differs between cultures.

However, the choices that one Muslim chooses to make should not impact what others should have to do. If one person chooses to put their religious salvation and struggles above their personal agency, that is that individual’s decision. That type of decision cannot be made for another person. To require someone to follow a certain Islamic belief is un-Islamic, and Mouftah provides a theological perspective as to how free will works within Islam.

“There’s this verse in the Quran that says there is no compulsion in religion,” Mouftah said. “So to actually require women to veil, then, might be at odds with other important Islamic values and teachings.”

Iran and other officially Islamic countries may claim to be Islamic republics, but their actions prove otherwise. Using oppressive forces against other people is unequivocally un-Islamic. Daiya also believes this and provided some further insight as well.

“When we’re talking about the Islamic Republic of Iran, I don’t think I’ve ever sat down and fully considered that to be an Islamic authority,” Daiya said. “It is the use of Islam [and] using religion as a way to oppress.”

In the world of Islamic politics, it is highly unfortunate to see so-called Islamic authorities support corrupt legislation and oppressive politics. Countries like Iran that manipulate their religious authority for their own perverted benefit are not Islamic.

Mouftah spoke on how Iran and Saudi Arabia are the two countries that have legislated dress codes. For many other Muslim countries, there is no established law on dress code, but it is highly common for women in these countries to choose to veil.

However, mandated dress codes and hijab laws do not exist exclusively to perpetuate forced modesty. Where women in Iran are forced to wear the headscarf, women in many European countries are denied the right to wear one. The policing of Muslim women’s right to choose to wear, or not wear, the hijab is threatened by many global powers. One of the most well-known examples of a country that rejects the right for women to wear the hijab is France. India has also recently introduced legislation that prevents women from wearing the hijab in academic settings. In the United States, wearing the hijab is not criminalized, but that does not mean that it is not highly stigmatized. Being visibly Muslim and wearing the hijab can be tough for a lot of Muslim women in Western countries.

Secularism is oftentimes the reason cited by most governments that ban the hijab. In France, the principle of laïcité originated in a 1905 law that supported the separation of church and state. Now, however, this principle perverted to support anti-hijab and Islamophobic sentiments throughout the country.

If the separation of church and state exists to ensure that no one is forced to follow religious beliefs that they do not adhere to, then is the lack of being able to wear the hijab not a violation of that? Is it not a violation of an individual’s personal liberty and religious freedom to not have the ability to practice their own religion, on their own time, in their own life as they wish to do so?

In secular Western countries, no individual Muslim woman is forcing other citizens to follow her beliefs by wearing the hijab. By wearing the hijab, I am practicing my religion in my own life, and this should not have an impact on anyone but myself.

Muslim women across the globe are placed in a situation where their ability to make decisions has been taken away. Mouftah brings up the importance of understanding the nuance of free will and personal agency within Islamic beliefs, but within the context of modern society, it is undeniably true that many women have been stripped of their ability to make decisions for themselves — whether that is to wear or not wear the hijab. Personal practice of Islamic dress code cannot be generalized and forcefully applied to an entire population. In a modern context, women should be able to choose whether or not they want to veil; that decision should not be in the hands of the state.

I actively choose to wear the hijab. It is a decision that I made, but it was most definitely impacted by various influences. My family members wear the hijab. My friends wear the hijab. Many important people in my life wear the hijab. I was gratefully surrounded by people that had a positive impact on my outlook on what it means to wear the headscarf, and that is an immense privilege that not all Muslim women have access to.

Amini’s death reminds us of the importance of letting women be able to make choices for themselves. Amini was a young woman with the entirety of her life in front of her, and she was murdered for something that the state should not have even had mandated power over.

Mandating headscarf laws on women through use of violence and force is blasphemous. Muslim women who want to wear the hijab should be able to do so without the interference of the state. Muslim women who do not want to wear the hijab should similarly be able to do so without the fear of any repercussions. Whether women choose to veil or not, they should be able to make that decision for themselves safely.

“That’s the question: whether to veil, or not to veil.” Mouftah said.