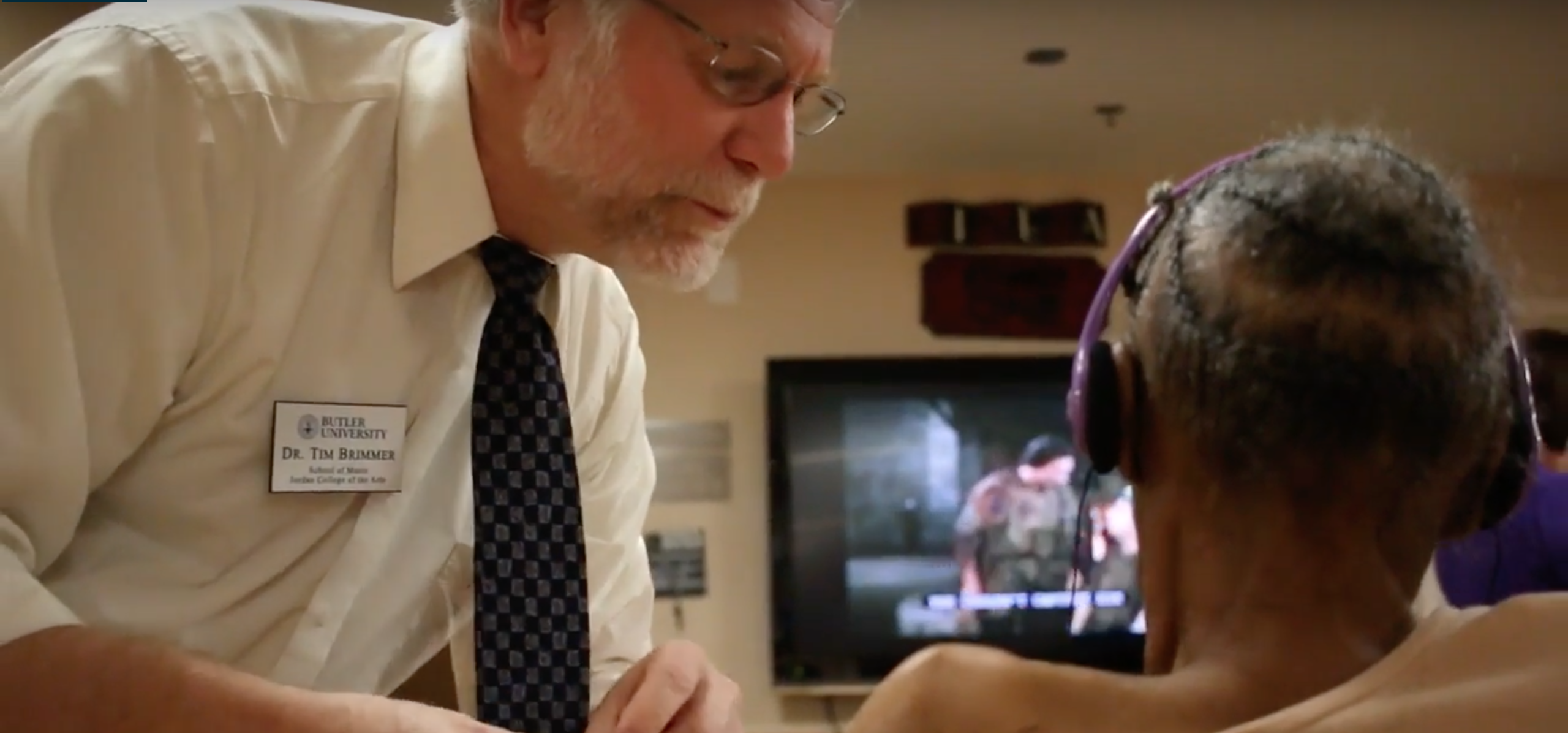

Dr. Tim Brimmer assists a patient with dementia. Photo courtesy of Mick Wang.

JESSICA LEE | CO-NEWS EDITOR | jelee2@butler.edu

During Emily Farrer’s ‘17 sophomore year at Butler University, she participated in a research project that combined music and science, young and old, care and treatment.

Farrer visited Harrison Terrace, a memory care facility, and played music for the patients in various stages of dementia. The music though, was personalized to every patient, playing music from their teenage years to their early twenties or music that the patients themselves or family members said they liked. After placing headphones on patients’ heads, she clicked play on the iPod shuffle.

Farrer remembered one woman who was in a wheelchair, always tightly hunched over.

“We started playing her Elvis music because her family members had told us she loves Elvis,” Farrer said. “It was the strangest thing. Her body was still hunched over, but suddenly she just started snapping, just one hand right along to the beat. It was crazy, like an automatic response.”

Farrer went on to study personalized music effects on patients with dementia for her honors thesis, but the research project she originally participated in expanded.

Now called Music First, the Indiana State Department of Health granted $600,000 to the research project. Butler first did three smaller studies as a group called Neuromusic Group, led by Tim Brimmer, music education and technology professor, and psychology professor Tara Lineweaver. Both professors still lead the Music First research.

Terry Whitson is the assistant commissioner for healthcare quality and regulatory at the Indiana State Department of Health.

“The ISDH was looking for ways to engage nursing home residents to improve their quality of life,” Whitson said in an email. “The Butler University Neuromusic Group was developing a project to achieve better health through music. The ISDH has funding for long-term care quality improvement projects and wanted to support Butler’s effort as a demonstration project for the state.”

Now, Music First’s immediate goal is to have 500 patients by July 2018; they currently have about 120 patients and continuously play personalized music and measure the effects. Specifically, researchers measure sundowning, when agitation and confusion may increase in the early morning and evening. Symptoms include restlessness, engagement level and repetitiveness. They observer patients’ rate of speech, physical movement and clarity of responses.

Kendall Ladd ‘16 is Music First’s research monitor data specialist. Ladd, along with memory care specialist Heather Johnson, recruits patients for the project and makes sure they meet certain standards. To participate in the research, patients must either have dementia, have prescribed medication for agitation, have an agitation episode documented over the past two weeks, or pass the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, which tests agitation.

Ladd and Johnson perform a baseline assessment, which includes cognitive assessments like the Mini-Mental State Examination and the St. Louis University Mental Status. They then build a personalized playlist with the participant, playing snippets of the song to see which ones they may like.

The playlist continuously changes depending on the patient’s reaction. If the reaction is negative, Ladd and Johnson replace the song. The goal is for patients to listen to music for 30 minutes and then Ladd and Johnson measure the sundowning symptoms.

Ladd said there is a sort of learning curve because positive or negative reaction varies person to person.

“I find myself having to go through this learning curve every time I meet a new person for the first time, just kind of learning about themselves and how they’re able to express how they’re feeling,” Ladd said.

A positive reaction could be singing and dancing or a more subtle tapping of the foot. Some patients may have aphasia or speaking deficit, Ladd said, so she has to be very aware of all their body movements.

While they will not have all the results until next year, some initial results have come in on a small portion of their participants. Ladd said the results, while very preliminary, have showed a significant improvement in patients’ MMSE scores, which measures cognition.

“It’s really exciting to see the numbers may actually confirm what we see on a day-to-day basis on a large scale,” Ladd said. “I think that’s something in research that’s really important — being able to use data analysis and these statistical tests to prove what you think you’re seeing.”

The assessments and measurements of the sundown symptoms allow the numbers of the quantitative research and the observations of the quantitative research come together.

Professor Lineweaver, having graduated from Butler in 1991 as a voice and psychology double major, has background in both science and music but is “a scientist at heart.”

Music First aims to answer questions with a scientific empirical study rather than anecdotal evidence. With a big sample size of 500 people, Music First hopes the results will be significant enough to prove personalized iPods will help those with dementia. A bigger goal is to have insurance companies, maybe even Medicare, pay for the iPods.

Donald Braid, director of center for citizenship and community, is the Principal Investigator of the research project.

Braid remembered telling Whitson from ISDH that one of his goals is to get Medicare to pay for iPods, and Whitson looked at him and said that might be possible.

“The research, the results, the goal of that is to help change the minds of those who set the protocol, who fund the insurance companies, the government in terms of Medicare and Medicaid, and to change what the treatment is to something that is a better way of handling,” Braid said.

In an email, Whitson said Music First’s work is an “important demonstration of an interdisciplinary approach to health care focusing on a collaboration on quality.” This “demonstration project” can be used as a template for future studies.

“An emerging priority in health care is a focus on quality of life as well as quality of care,” Whitson said. “A conversation on aging is essential to identifying each resident’s goals and priorities. The music project provides a means to engage residents.”

Braid said the quality of care in terms of treatment, such as pharmaceutical drugs, may be well implemented in the health care system, but maybe not quality of life.

Medications that treat dementia can cause increased confusion, damage cardiac function and have other harmful side effects on how long patients can live, Lineweaver said.

Braid said sometimes medications can pull patients “further away from themselves and functionality.”

Even after months of research, Farrer said she was still uncomfortable interacting with patients.

“To see someone with dementia, it’s like they’re not even a person anymore — it’s like they lost so much of themselves there’s no one to talk to,” Farrer said. “I love that internal interaction with people and I could never achieve that with them; I never felt like I was reaching out to them. … It was also painful to make friends with them one day and make friends with them the next day too.”

A natural world course called Neuromusic Experience sends students to perform the same study. The course, while it does not add to the Music First research, is a way to introduce students to the study and perhaps draw them to the research project. The course fulfills Butler’s Indianapolis Community Requirement.

Braid, who oversees the ICR courses, said Neuromusic Experiences fulfills the requirement because it ables the students to connect with a broader community.

Braid said he does not like it when ICR courses are about students going into the “real world.”

“I don’t like that because I think you’re in the real world now,” Braid said. “What goes on here matters, it’s not some fantasy land. And a colleague of mine at one point said, ‘You’re in the real world now, but there’s more of it beyond the campus boundaries.’”

Tonya Bergeson-Dana, communication science and disorder assistant professor, teaches the course alongside professor Lineweaver.

“We try to set expectations for the students,” Bergeson-Dana said. “We have orientations with nursing home directors, just try to set the stage. … And the nursing homes in general are different kinds of places than they typically may go into. So we have a mixture of expectations from our students; some students expect the worst, and some students expect the best.”

Jessica Hock, sophomore elementary education major, took the class her first semester at Butler. She said if you have never been in a nursing home, it can be a bit scary and sad; some people just sit in the common area or wander around the halls. Typically, activities are available for the patients.

Bergeson-Dana said seeing the effects of dementia of first hand is “heartbreaking.”

“But then, to have the opportunity to place the music through the headphones and see their faces light up and see them remembering something and feeling like they have control over something and can do something positive is really fantastic,” Bergeson-Dana said.

Hock said one of the patients she worked with reminded her of her grandmother, who died of Alzheimer’s.

“You would play music for her and she would just change completely,” Hock said. “She would just start dancing and singing along to the music and then she would start telling stories about her childhood.”

Braid said a student once asked, “Does it matter if I’m helping someone, if they don’t remember the next day?”

What matters, Lineweaver said, is the moment. Many of the patients live in the now.

“[Students] out there with the older adults, doing the music listening, watching them light up, watching their day get better because we’re there and watching those connections and knowing we’re having a positive impact on people’s lives regardless of how long it lasts,” Lineweaver said. “Whether it’s a better moment in their lives or whether it’s a better year in their lives, it’s still worth the time and effort to have that positive impact.”

Braid said students come back with a greater understanding of the importance of interacting with older adults, many of whom are put in nursing homes and are not seen by younger generations.

“It’s a matter of, if we start understanding and empathizing with other human beings,” Braid said. “We want people to live lives with dignity, we want people to live lives of meaning and value, and to sort of preclude that by medicating and hiding away is a problem.”

To engage with any community that is different than the students’ is “to recognize that sense of common humanity,” Braid said.

“There’s an intentionality there in terms of making those kind of connections,” Braid said. “This is one of those places where students connect with the elderly, understand how this stuff matters that connects their heads and hearts.”