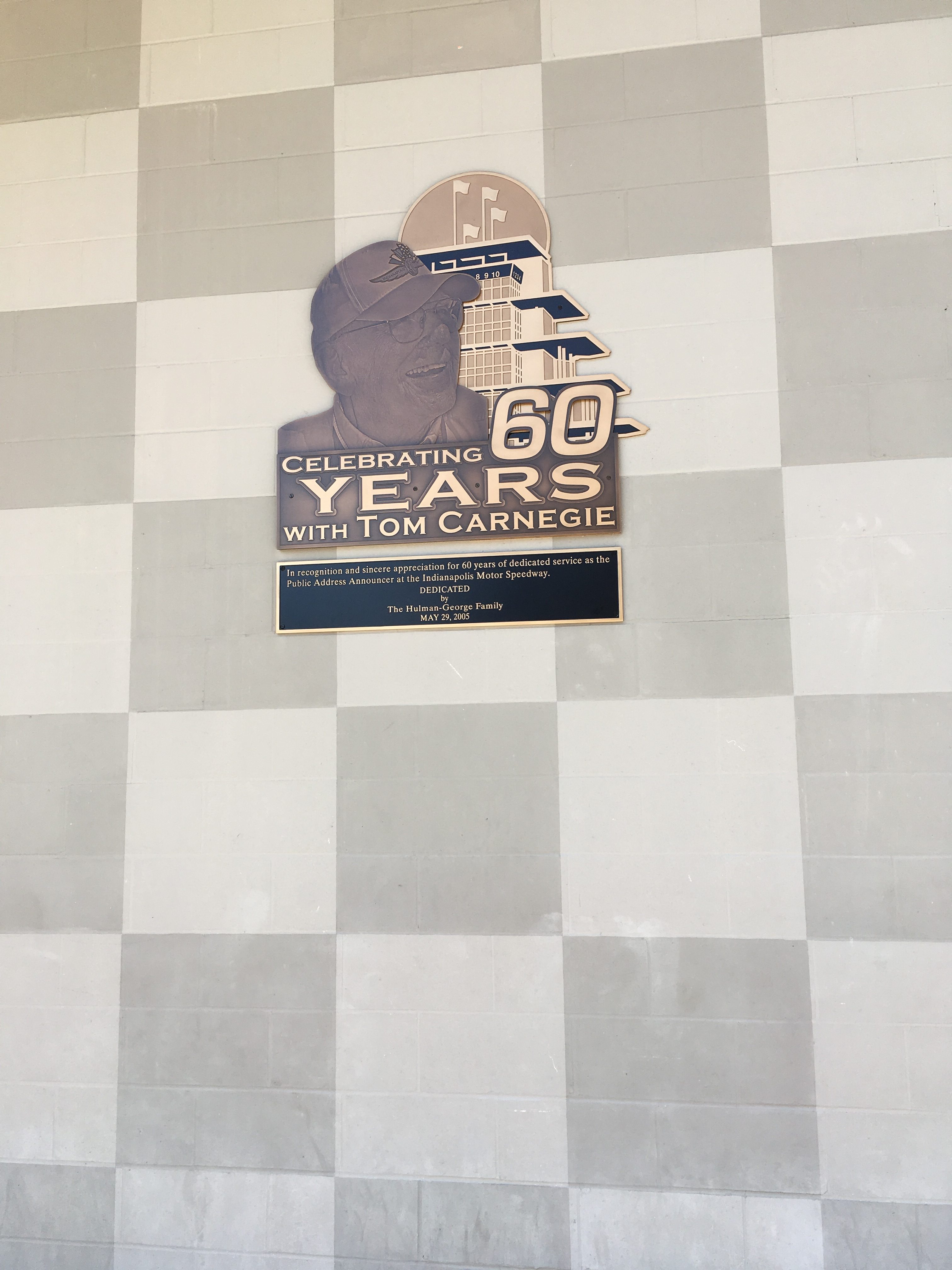

A plaque mounted to one of the grandstands at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway honoring Tom Carnegie’s more than 60 year dedication to the speedway. Photo by Zach Horrall.

ZACH HORRALL | SPORTS CO-EDITOR | zhorrall@butler.edu

For 61 years, fans flocked to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to hear not only the cars whizzing around the track, but the voice coming from the PA. Coming from Tom Carnegie. He lived a storied life that took him to Indianapolis by chance. There, he fell into a roll at the track, worked at a television station and taught at a university along the way to numerous hall of fames.

Because of being in the news and at school, Carnegie was known in the Indianapolis community, and in the 1960s, his voice began to claim fame at the track. But from a racing perspective, it took years for him to bask in the glory like he did in his later years.

The reason it took so long for his face to be associated with his voice is because he hid from the fame for years. Carnegie was diagnosed with polio while in his late teens and suffered from constant pain.

“He was in pain a lot of the time, and he used leg braces,” Indianapolis Motor Speedway historian Donald Davidson said. “As he walked, you could tell that it was a great strain. And you could hear all the springs moving and creaking, and he used a cane, so he pretty much kept out of the limelight.”

Carnegie actually never wanted to go into sports announcing. He was fascinated by theatre and wanted to go into acting. However, polio kept him from achieving his dream. After he was diagnosed, he knew that someone with polio would never make it on the big stage. So, with that in mind, he pursued sports. He had a great voice, and he let that lead his future.

Carnegie started his career at the track in 1946 after he had recently moved to Indianapolis from Fort Wayne.

“He was the first guy to do local television,” Dave Calabro, the man who is now in Carnegie’s position at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, said. “He used to tell me stories about a guy from Indianapolis called him while he was doing radio in Fort Wayne who said, ‘Hey we’re going to do this new thing called television where you talk into a camera and people will see it in their homes.’ So he took a chance and came down here and was the first guy on television in Indy.”

How he got his start at the track, according to Davidson, is that he was doing the public address for a car show when Wilbur Shaw, a three-time Indianapolis 500 winner and former track president, told him to come to the track and do the PA for the Indianapolis 500. Carnegie agreed, and showed up on race day to call the race.

Away from the track, Carnegie had a full-time job as a sportscaster. He hopped around for a while between radio stations before he found himself at Channel 6 news, then WFBM and now WRTV, as the station’s sports director.

Outside of that, he was in the classroom at Butler University teaching a sports casting class every other year, as well as running the radio department at the university.

The music department at Butler operated the university’s first radio station, WAJC, which was located downtown. Carnegie helped start it, and then ran it for several years.

Carnegie was known on campus as a fun professor who made class fairly easy. Greg Lucas, a Butler graduate who went on to become a hall of fame announcer in Texas, said he rarely had class in a classroom.

“He would take classes to the track, to basketball games and to high schools to shadow,” he said. “We were [mainly] in the radio station or at Channel 6. That was great.

“He was a very good teacher for what he taught. He really enjoyed passing on his knowledge. You took [his class] because you wanted to be in the field. Others took it because he wasn’t going to be hard on you. You knew you were going to get an A or B.”

Barry Hohlfelder, a longtime producer in the Chicago area and Butler graduate, took Carnegie’s class not because he needed it, but because he wanted to see Carnegie in person.

“I have no idea why I would be in that class,” he said. “You just couldn’t believe you were sitting in class with this legend. It was an opportunity of a lifetime.”

As a professor, Hohlfelder said Carnegie was there because he wanted to be there and cared about teaching.

“He was very open, accommodating and interested,” he said. “There were no stupid questions. He had respect and genuinely cared about those with interest.”

Carnegie left his mark on those students he had. Both Hohlfelder and Lucas learned things they used in their careers.

“What I really took away from class was how to project with words,” Hohlfelder said.

Lucas, who went into a field that Carnegie more prepared him for, said he was one of his biggest mentors.

“For what I ended up doing with my life, I took a lot from him,” he said. “It was such little things: give the score, beat the crowd to the punch, expand your vocabulary, but not getting too colorful. He was a great mentor for anyone who wanted to go into the field.”

His voice fascinated millions of people. And Carnegie didn’t just announce what he saw on track. He played with the crowd, worked them up and created catchphrases along the way. Because he couldn’t pursue his dream of theatre, he tried to bring theatre to racing.

“He told me in that booming voice, ‘It’s theatre, Donald, its theatre,’” Davidson said of how Carnegie worked the mic. “He had a great sense of the dramatic and theatrics. Not that he was making it up, but he liked to be able to work the crowd.”

As for the catchphrases, even to this day, they are still extremely popular, and he is still impersonated. “It’s a new track record,” “Let’s wait and watch,” “Here he comes,” “And it’s still faster” and “And he’s on it” are some of the many phrases fans and announcers recite to this day.

Even the simplest things would make the fans at the track go crazy. Like for instance, mic checks.

“The gates to the track would open at 6 a.m., and the PA would start at 8, and you would hear a click, a hum and then ‘One, two, three. Testing. Good morning ladies and gentlemen,’” Davidson recalled. “And there would be this huge roar, and I thought ‘Good golly, only Tom Carnegie could get an ovation for a sound check.’”

Because the crowds started growing when Carnegie’s voice became popular, Davidson ranks him in his top-10 most influential people in Indianapolis Motor Speedway history.

“I personally think he is the one guy that did the most to build the crowds,” Davidson said. “He’s way high on my list of the most significant people in the history of the track,” he said. “It’s Carl Fisher and Jim Allison are the two main partners, and then Tony Hulman and Wilbur Shaw, jointly, Eddie Rickenbacker, A.J. Foyt, Al Unser, Mario Andretti, Sid Collins and Tom Carnegie.”

As the years went on, things began to change for Carnegie personally. He decided to try to get in better shape. He began to swim, started doing acupuncture and had surgeries to try to correct the polio as much as possible. After the surgeries, Carnegie was able to get rid of the leg braces and walk on his own. It was then that Carnegie opened up to the public and started accepting his fame.

“All of this seemed to change his personality, because the pain was lessened,” Davidson explained. “For the last 20 or so years [of his life], he was very available and open and very gracious, because they kept thanking for him for what he had done. He liked the fame.”

In the 1980s, Carnegie’s career also started to change. In 1985, he retired from Channel 6 and did solely the PA at the Speedway. That same year, he also brought in a young college kid to help him with the PA. That young college kid was Calabro, who would work next to him for the next 21 years.

“He was my mentor,” Calabro said. “He took me under his wing, and I learned so much from him. He was one of these gracious guys who was a Butler guy. This guy was one of the legends of broadcasting.”

Not only was Carnegie a legend, but he spent his life with legends. And not just racing legends. Calabro remembers that Carnegie was a great story teller and had a lot to tell.

“It was fun to be around him and listen to all the stories he had,” Calabro said. “I went to take him to lunch one day and was throwing a baseball in the air as I waited. I looked at the baseball and realized it was autographed by Babe Ruth. It was just laying on his desk. I was like, ‘Hey. You might want to put that baseball up because one of your grandkids could go to college on that.’ All of a sudden, he started telling about the day he got to go to dinner and had a beer with Babe Ruth.”

Calabro stayed dedicated to Carnegie and the Speedway, and he eventually took over the spot as chief announcer after Carnegie decided to retire in 2006. However, out of respect for Carnegie, the track has never officially named another chief announcer.

“Stepping into that role was different because he’s a once in a lifetime talent, I think,” Calabro said. “I never try to be him. I try to be Dave.”

After debating it for some time, Carnegie decided after Sam Hornish Jr. edged out Marco Andretti at the line in the 2006 Indianapolis 500 that he wanted to end on a good finish and retired from announcing.

“I’m glad that in the later years he was around to hear the accolades that some of us were able to say [and he was able to receive],” Davidson said.

Hohlfelder remembers an Indianapolis 500 media day after Carnegie retired where the track brought Carnegie back for the younger drivers and media to meet him and have time to talk to him.

“You could just tell it meant so much to him,” Hohlfelder said. “He had a standing ovation, and you could just tell everyone there truly appreciated him.”

Throughout the years, Carnegie received many awards and honors for his work at the track and on television. Most notably, he has been inducted into the Indiana Journalism Hall of Fame, Indiana Associated Press Hall of Fame, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame and the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame among other accolades.

Carnegie gave in to his age and health issues in 2011 when he passed away at the age of 91.

Polio took from Carnegie the dream of performing on stage. However, he did get to be on the stage at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The fame didn’t come to him like it did in his dreams, but nonetheless, still to this day, racing fans around the world rejoice when they hear his legendary voice.

This is part four of a four-part series highlighting Butler University’s connection to the world of auto racing.