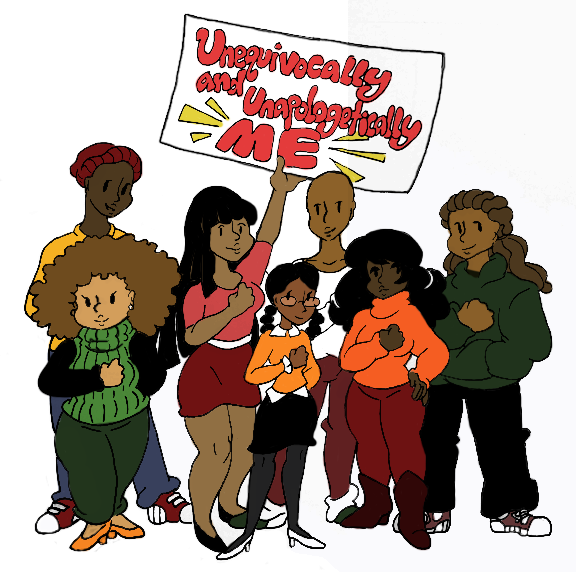

Illustration by Camille Bates

CAMERON ALFORD | CONTRIBUTING COLUMNIST

“To handicap a student by teaching him that his black face is a curse and that his struggle to change his condition is hopeless is the worst sort of lynching.”

Carter G. Woodson made this statement referencing the miseducation of black students in America in his book, The Miseducation of the Negro. It seems that many black students are not acknowledged or valued for their blackness in their school environment.

Their voices need to be heard.

All students have plenty of accredited colleges and universities that they can choose from to spend their next four to six years. That number one choice is based on specific criteria that makes the school the best choice for them.

But in the black community today, we are faced with an extra choice: whether to attend a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) or a Predominately White Institution (PWI).

Both types of institutions provide an education through accredited colleges and universities, but not necessarily the same education.

The issue of black students going to a PWI versus a HBCU institution has plagued our community for years. But does it really matter which type of institution you attend as a black student?

Chelsea Cooper, a junior political science major at University of North Texas in Denton, views college as an institution that helps her receive the degree she expects to acquire.

Noticing the injustices that have been brought to the table through the #BlackLivesMatter movement, she said she is determined to become a lawyer because the black community needs more black lawyers.

Cooper said her education is important, but she does not think the degree alone will help her succeed.

Obtaining the degree will open the door for her to make a profound impact as a future lawyer. That is what is necessary for her.

But simply going through college and all of its experiences just to receive a degree is not enough for some students. Some black students attend PWIs because of the necessity to experience people outside of their race.

Li’Yonna McCallum, a first-year journalism student at Butler, said she loves HBCUs, but realized it was not the kind of environment she desired to be in.

She said she wanted to be in an environment where she could experience people from different races, backgrounds and ethnicities, which she knew would present a level of discomfort for her.

But for McCallum that discomfort is necessary.

“For me to be uncomfortable is a trigger for me to open myself up to learning new experiences,” she said.

She said being uncomfortable at Butler keeps her aware of all of the things she does not know, and helps her adapt to and embrace what she is learning, in and out of the classroom.

For Arisa Moreland, a first-year secondary education major, going to Butler was an opportunity for her to develop strategic connections within the Indianapolis community—the community she holds dear to her heart.

Moreland has made it her purpose to positively impact the lives of students through teaching, specifically for those in this area.

She credits her drive to the first black teacher that she had in seventh grade. Moreland said that the teacher played such a huge role in her life because she was honest about what it meant to be black in America.

“She was just so open, caring, and easy to connect to and learn from that I knew I wanted to do something the way she was doing it,” Moreland said.

From that moment, she knew she wanted to be a teacher, and it was necessary for her to go to Butler and take advantage of the connections in Indianapolis that the education program provides.

I believe education is necessary in order to change the world around us.

But “to change the world, you can’t be afraid,” David McNeal, a sophomore political science major, said.

In high school, McNeal was part of history by attending one of the all-boys public schools, Urban Prep Academies, that sent 100% of their students to college. Because of this organization, McNeal was taught to change the world as a black male.

He was faced with the choice of attending Howard University, a HBCU in Washington, D.C., or Butler University, a PWI in Indianapolis.

He chose Butler.

Since he has been at the university, McNeal has overcome a lot of challenges in his new environment. But he said the opportunity to observe some inequalities on campus were necessary for his development.

McNeal credits his resilience to knowing his history.

“Knowing more about your history keeps you aware of who you are and breaks mental barriers,” he said.

For Kandia Moore, a junior advertising and strategic communications student at Howard University, knowing her history is something she embraces every day on campus.

“Your environment does shape you,” she said.

What she finds valuable about the education at Howard is that she is exposed to her history from before slavery.

“If you think your history starts from you being a slave, versus your history starting with you being a queen or king, it is a completely different perspective,” she said.

There are so many misconceptions about HBCUs, but Moore said that HBCUs teach you how to value yourself as a black person.

“Learning so much about where you come from is very empowering,” she said.

Even though school spirit is at varying levels at each of our institutions, it is imperative that we are aware of why we attend the colleges we choose to attend.

Maia Butler, now a teacher for Citizen Schools, attended Hampton University, a HBCU in Hampton, Virginia.

She grew up in a predominately white neighborhood and went to predominately white schools growing up, but she wanted to be surrounded by individuals that shared a common identity.

At Hampton, Butler said she was able to embrace who she was.

These students expressed why they chose to receive their education at their specific institution.

All of them are proud of their choices, no matter the flaws and issues they find in their universities, because they know why they are attending the school that is right for them.

So, does it really matter where a black student receives their education? I will say no.

Carter G. Woodson said that education is not what is given to you, but what you go out and acquire.

“Those who have not learned to do for themselves and have to depend solely on others never obtain any more rights or privileges in the end than they had in the beginning,” Woodson said.

It is not about where you receive your education, but how you value yourself and your history that makes real education powerful.