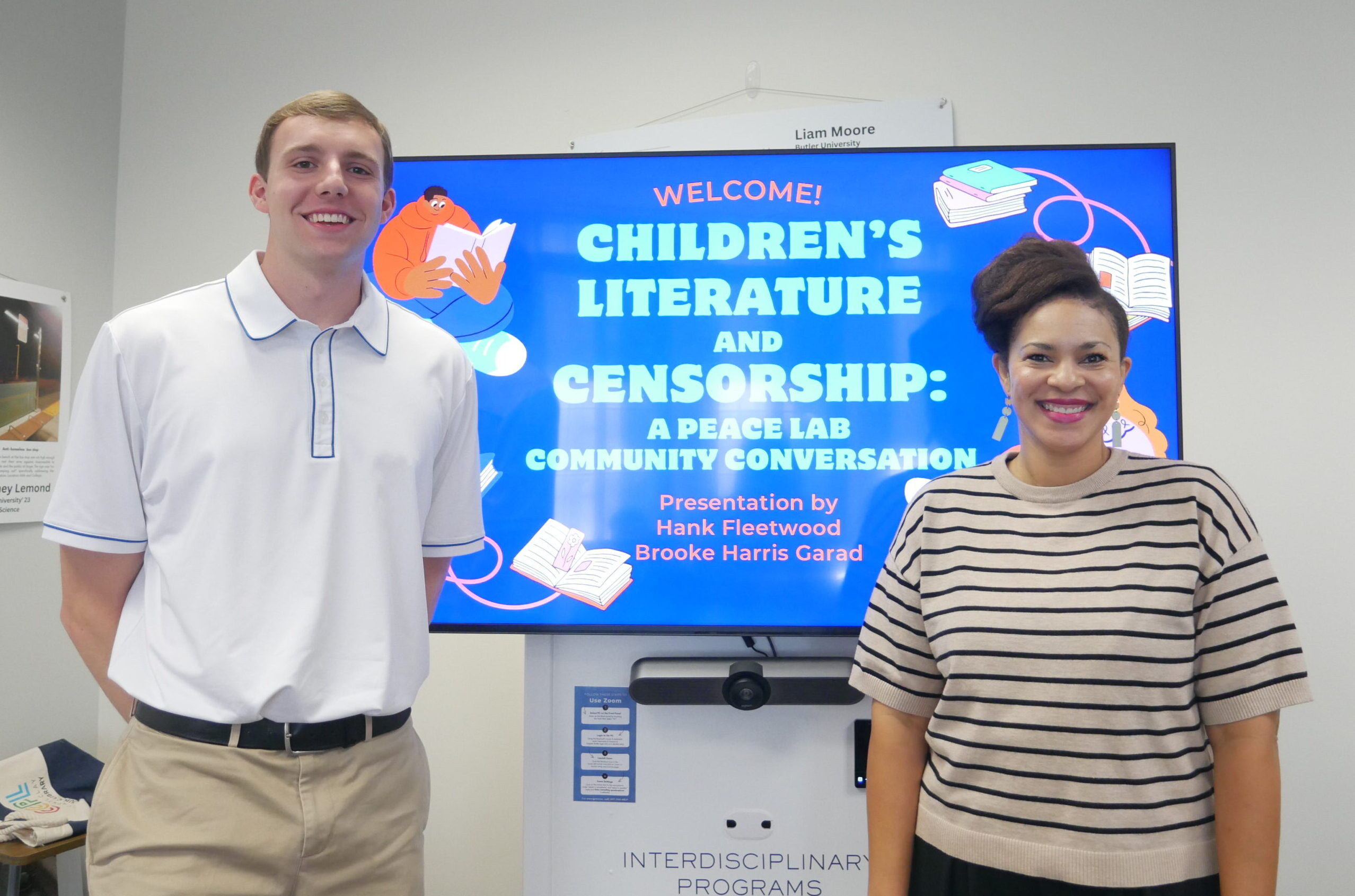

Brooke Harris Garad and Hank Fleetwood presented their research and sponsored a community conversation on censorship in children’s literature. Photo by Ally Swearingen.

KATE NORROD | STAFF REPORTER | knorrod@butler.edu

The Desmond Tutu Peace Lab hosted a community conversation centered on censorship in children’s literature on Oct. 10. The event consisted of a research summary, conducted on banned and challenged children’s books, followed by a Q&A discussion.

Brooke Harris Garad, an assistant professor of education, and Hank Fleetwood, a senior political science major and Peace Lab intern, shared their findings from a joint research project. They were also assisted by Butler alumna Grace Erickson.

Literature censorship involves the banning and challenging of certain books. When books are banned, they are removed from the shelves of libraries, bookstores and classrooms.

Harris Garad shared concerns about the social dynamics behind book banning. Debates and discussions revolving around free speech and expression have recently risen in the United States.

“We’re in a very interesting sociopolitical time,” Harris Garad said. “I would argue we’re really negotiating this idea of what free speech means and this idea that we all have the ability to censor others when they speak about things that we don’t like.”

During the event, Harris Garad and Fleetwood dissected a multitude of children’s books and presented three: “And Tango Makes Three”, “Something Happened in Our Town” and “Julián is a Mermaid”. All three books, though very subtly, have been found to challenge traditional American values like respect for authority and heteronormativity, among others. They also found that marginalized and minority communities are disproportionately targeted in book bannings.

“When you’re banning books — oftentimes these books feature characters of color or LGBTQ+ characters,” Fleetwood said. “When kids do not see themselves in what they’re reading, then they feel less comfortable with their own identities.”

Harris Garad’s background as an educator allowed her to corroborate the consequences of book banning. She also shared her perspective as a parent. She spoke about her daughter’s fourth-grade class, which includes two students who identify as LGBTQ+.

“There’s a decrease in empathy, which I think is a key component of peace in the world,” Harris Garad said. “There is [also] the risk of children not feeling comfortable in their own skin, and I think that’s really a sad reality and a responsibility of educators to help children feel seen, heard, and valued.”

Hannah Moser, a junior English education major, had prior experience with censorship and banned books during high school, but was unsure how that could relate to children’s literature.

“As a future educator, [I] would want to make sure my [students] are represented in the literature I have in my classroom,” Moser said. “I would love to be able to include diverse texts and texts that represent them as people into my curriculum and their learning.”

From the perspective of a professor, Harris Garad wants to ensure that education students like Moser are well-equipped for professional struggles they might face relating to book banning and freedom of speech.

“I feel, as a professor in the college of education, that I have a responsibility to prepare students for some of the challenges they might face in their profession — the idea of having children’s literature in their classrooms [that] can bring them under fire from their leadership or from the parents of these children in their classroom,” Harris Garad said. “I think it’s important that they know some of the history and just some of the ways to navigate how they can support their kids and also keep their jobs.”

Harris Garad, Fleetwood and Moser all expressed that bringing publicity and awareness to the history and effects of book banning are crucial to helping stop it.

Fleetwood noted that book banning often backfires and sales of the books skyrocket thanks to increased media coverage, which helps to fight censorship.

“What we’ve seen is that when a book is challenged, and it comes up in the news, that’s really a financial boost, and it drives interest for that book,” Fleetwood said.

Fleetwood encouraged combating censorship by showing up to public hearings for book bannings and expressing disagreement.

Protesting the banning of books, alongside advocating for literature that represents a wide range of students in classrooms will help promote overall education and could encourage students to read books that reflect their lives and stories.