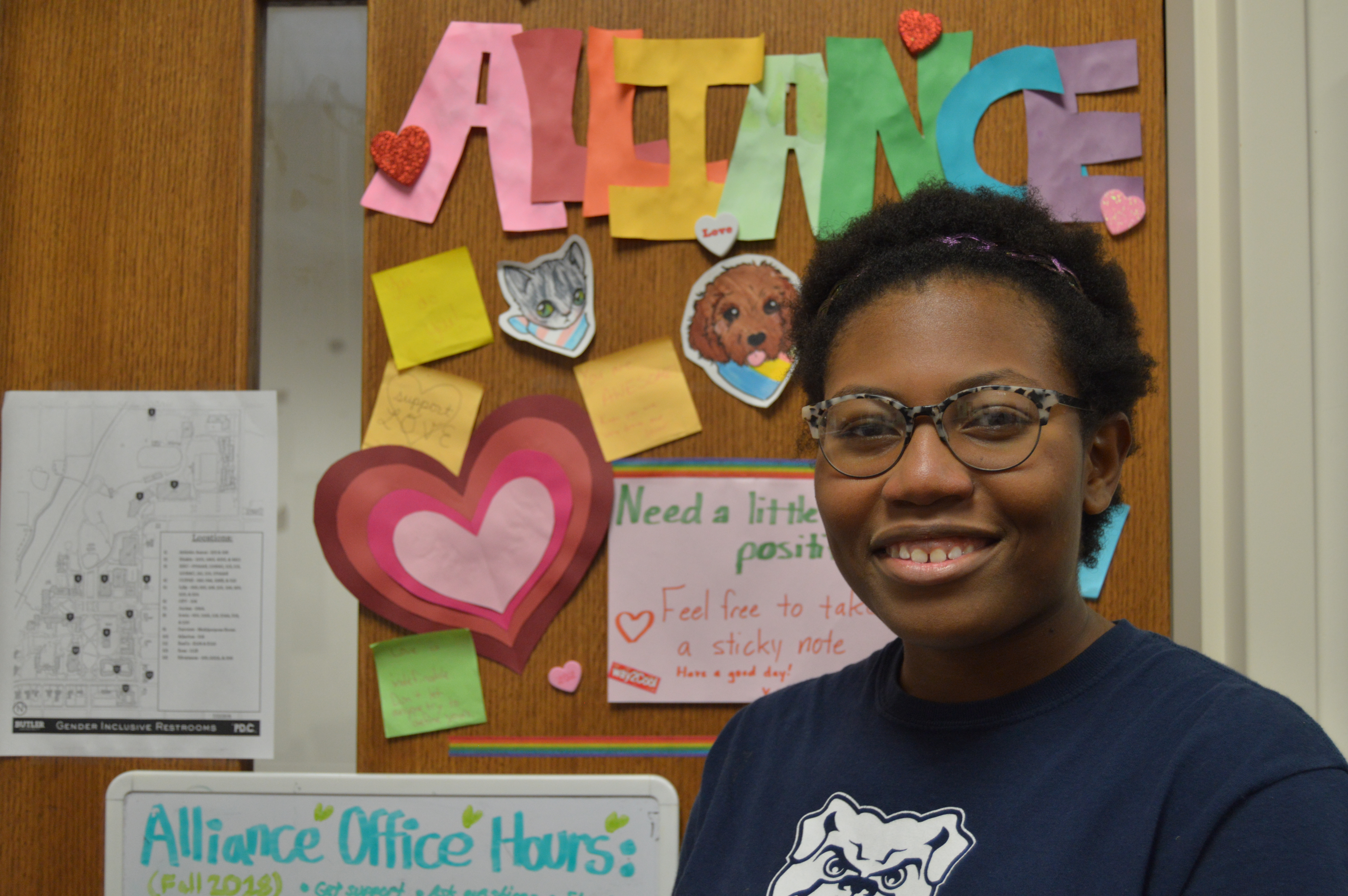

AJ Mathews is the president of Alliance, an LGBTQ+ group on campus. Photo by Regan Koster.

CAMILLE ARNETT | STAFF REPORTER | carnett@butler.edu

Obergefell v. Hodges was decided by the Supreme Court in the summer of 2015. As a result of the case, current Butler seniors entered college with the advent of legal same-sex marriage in all fifty states, Indiana included.

But the equal legal treatment of homosexuals and bisexuals has not ended discrimination against members of the LGBTQ+ community.

Over the past few years, improving diversity at Butler has been a frequent topic of campus conversation. The experiences of queer people on campus can speak loudly to the ways in which Butler as a whole needs to improve.

The mixed attitudes towards queer people on campus, combined with a small and often concealed queer population, makes the college experience for a queer student different from that of a cisgender and heterosexual student.

Campus atmosphere is a subjective experience, and identity plays a large part in how someone experiences Butler from the day-to-day. From one side of the fence, campus appears to be an unabashedly welcoming and accepting place, but for queer people, it’s different.

Gianna Kujawski is a senior English major, as well as a bisexual woman.

“On this campus, there’s this feeling of, ‘OK, we know you’re there, but we’re not going to acknowledge it or talk about it,’” she said. “There’s no definitive label for it, but it’s still there… we don’t want to acknowledge that because we’re living in 2018 and we’re supposed to be OK with this. But are we?”

The concept of abstract discrimination is felt by other queer students across campus.

AJ Mathews is a senior human communication and organizational leadership major. They identify as genderfluid, which they define as feeling “some of everything we think of as gender.” Matthews is also the president of Butler Alliance, the registered club for LGBTQ+ students and their allies.

“Butler is liberal for Indiana, but a good chunk of the campus is conservative,” Matthews said. “Nobody is overtly homophobic… everyone does it covertly, they do stuff where you have to be of the marginalized group to notice the microaggressions that people do… it’s an undercurrent.”

Microaggressions are comments or actions that express a prejudiced attitude towards a marginalized group of people. These gestures are often unintentional; however, the culmination of experiencing such microaggressions can be exhausting.

Kasey Meeks is a senior health sciences and chemistry major who identifies as bisexual.

“Butler is not a very diverse place, I don’t think that’s a secret to anyone,” she said. “The thinly-veiled [prejudices] that you see on campus are things that, if you ask the people doing them, they wouldn’t have any idea. A lot of people, if you asked them, ‘Hey, what do you feel about gay marriage and gay rights?’ they’d be all for it. But they are not aware their actions are telling a different story.”

Experiencing covert prejudice and microaggressions is common among transgender students. Transgender rights have only entered the prominent cultural conversation in the last decade, so many people are still behind the curve in knowledge about transgender people and their struggles.

V, who asked to be identified by initial only, is a senior non-binary student who said: “You’ll have people knowingly misgendering [trans] people, not respecting them, making jokes that clearly have a legitimately transphobic edge behind them. In most cases, jokes at the expense of a marginalized group do have prejudice behind them. It’s a way of delivering those prejudices in a way that’s more socially acceptable.”

Social problems for queer people on campus are also impacted by the structural makeup of Butler. There is no official data on the queer student population at Butler, though the Alliance roster of out queer students comprises about 3 percent of the student body. Though that figure does not include students who are openly members of the LGBTQ+ community, it puts in perspective how small the queer population is on campus and why there is a desire to create support circles that come from a place of shared experience.

Sam Varie, president of the Student Government Association and a gay man, spoke to the importance of queer friend groups.

“I tend to gravitate towards people who are queer because I don’t have to fear homophobia or microaggressions or aggressions,” he said. “I’ve worked with people throughout my three years who are on a journey of understanding and coming into their own with their sexual orientation or gender identity… I’m glad I’ve been someone who people could confide in and could be their ally.”

The importance of these spaces can’t be understated, especially for students who come out in college like Kujawski.

“There is that group of people [on campus] that is understanding and accepting,” she said. “If you find those individuals… and surround yourself with those individuals, then the community really helps each other flourish.”

Around campus there is minimal physical acknowledgement of the LGBTQ+ community. Pride indicators like flags, marketing materials and T-shirts are slim to none. The most consistent evidence of LGBTQ+ students around campus is in the Alliance office in the Diversity Center, or Safe Space signs.

So how can a student find these queer communities to squeeze themselves into?

If a student is looking to join a club, they can attend Alliance meetings. If not, another important facet of college life is finding mentors and peers to look up to and bring younger students into the fold.

Alliance president Matthews attends events for the benefit of other LGBTQ+ students who may be daunted by the campus.

“I make an effort to make people feel comfortable,” they said. “I’m at everything, and I’m going to tell everybody that I’m right here. Just being here, just being that little queer beacon… I’ve learned to force myself into spaces and not care… I want to make sure [people] see me.”

Hunter Wheatcraft is a junior music performance major and bisexual transgender man. Photo by Regan Koster

Hunter Wheatcraft is a junior music performance major and a bisexual transgender man. He has reaped the benefits of having queer people in his community over the course of his experience at Butler, particularly in Jordan College of the Arts.

“In the music school, there are a lot of older students interacting with first years in ensembles,” he said. “Seniors who are used to being gay — all over the place — you get to see that in JCA.”

Having strong communities where LGBTQ+ can help foster self-acceptance stresses the importance of the social and mental health of students. But because the queer community on campus is so small, there is pressure to preserve the sanctity of these groups, and that has a direct influence on dating.

Meeks described the queer dating scene at Butler, particularly for women and non-binary people, as so small and tight-knit that it teases nonexistence.

“It’s the same people, dating different people of the same group — and it reminds me of high school, the overlap,” Meeks said. “If you tell me the name, particularly with queer women, of someone on this campus, I can probably tell you everyone they’ve dated.”

V described a similar phenomenon.

“You get these close-knit groups, partly because there aren’t that many openly-queer people on campus, and you don’t want to potentially mess up that dynamic,” they said. “There are only so many people who know I’m non-binary and therefore would be okay with dating a non-binary person.”

Trying to explore dating with such a limited group of potential partners can be disheartening, and it takes away from the college experience.

“Everybody is really adamant about not dating anybody else from Butler,” Mathews said. “Everybody has this fear of, ‘What if it doesn’t work out, and what if I have to see this person everywhere on campus?’… It becomes anxiety-inducing.”

This fear extends into the structural problem of dating around campus. For students in the closet or still coming into their identity, having a public dating life is a potential personal security risk.

“It’s hard to even be open about who you are on this campus, so how do you pursue a significant other?” Kujawski said.

Queer social and dating culture is tied to the larger campus environment. If the campus doesn’t feel especially welcoming to queer students, that fear of rejection can influence how they feel they can safely date on campus.

For gay and bisexual men, there is a more active dating scene, especially with social media. But many interactions happens in great privacy and with anonymity.

“There are people on Butler’s campus who are on Grindr and purposely don’t have a picture,” Wheatcraft said. “People who are maybe not out or maybe coming to terms with it, message first and lay it all out on their terms. In those cases, it’s wanting to do everything gay that’s not out in the open.”

Varie agreed and said, “Being discreet is very prominent in the LGBTQ+ community, especially in the gay man community. It’s rooted in uncertainty and fear. The uncomfortability with having to question your identity.”

Butler is a small school in a city with only pockets of queer culture, all wrapped up in one of the most consistently red states in the country. This creates built-in problems for queer people in their everyday lives. Though microaggressions may, by their name, seem inconsequential, it is the compound of factors that contributes to an experience that — just as often as it can be fulfilling and exciting — can be stifling and isolating.

Varie emphasized the importance of meeting students where they are to help educate the campus about LGBTQ+ issues, in hopes of making the campus a more informed, welcoming space.

“All of us have blinders on,” he said. “If something is not poking at us or affecting us, it’s hard for people to have that empathy—to go and learn what they don’t actually know they don’t know.”

Ultimately, Butler can be a good, safe place for LGBTQ+ students, but the overall campus atmosphere lacks awareness of queer existence on campus, and that seriously affects queer students’ social lives. Because social life is not just the people you choose to surround yourself with, but the people you are forced to be surrounded by.

Varie stressed the importance of Butler making its resources known to entering students, as many still aren’t aware of the options.

“Students should come to Butler understanding the resources available,” Varie said. “LGBTQ+ resources should become ingrained pieces of our Butler community. Otherwise, it will be an addition.”

Kujawski seconded the need for acceptance.

“There needs to be more conversation and more open dialogue,” she said, “about identities and who we are as people—and hopefully through that, you breed acceptance and inclusivity.”