Cultures of body shaming and misogynistic behavior have cemented themselves in the digital world. Graphic by Elizabeth Hein.

LEAH OLLIE | CULTURE CO-EDITOR | lollie@butler.edu

As the pendulum of public opinion swings to and fro regarding women’s rights, celebrity culture and reckonings of accountability for sexual harassment and misconduct, social media still cultivates pockets of negativity that objectify women.

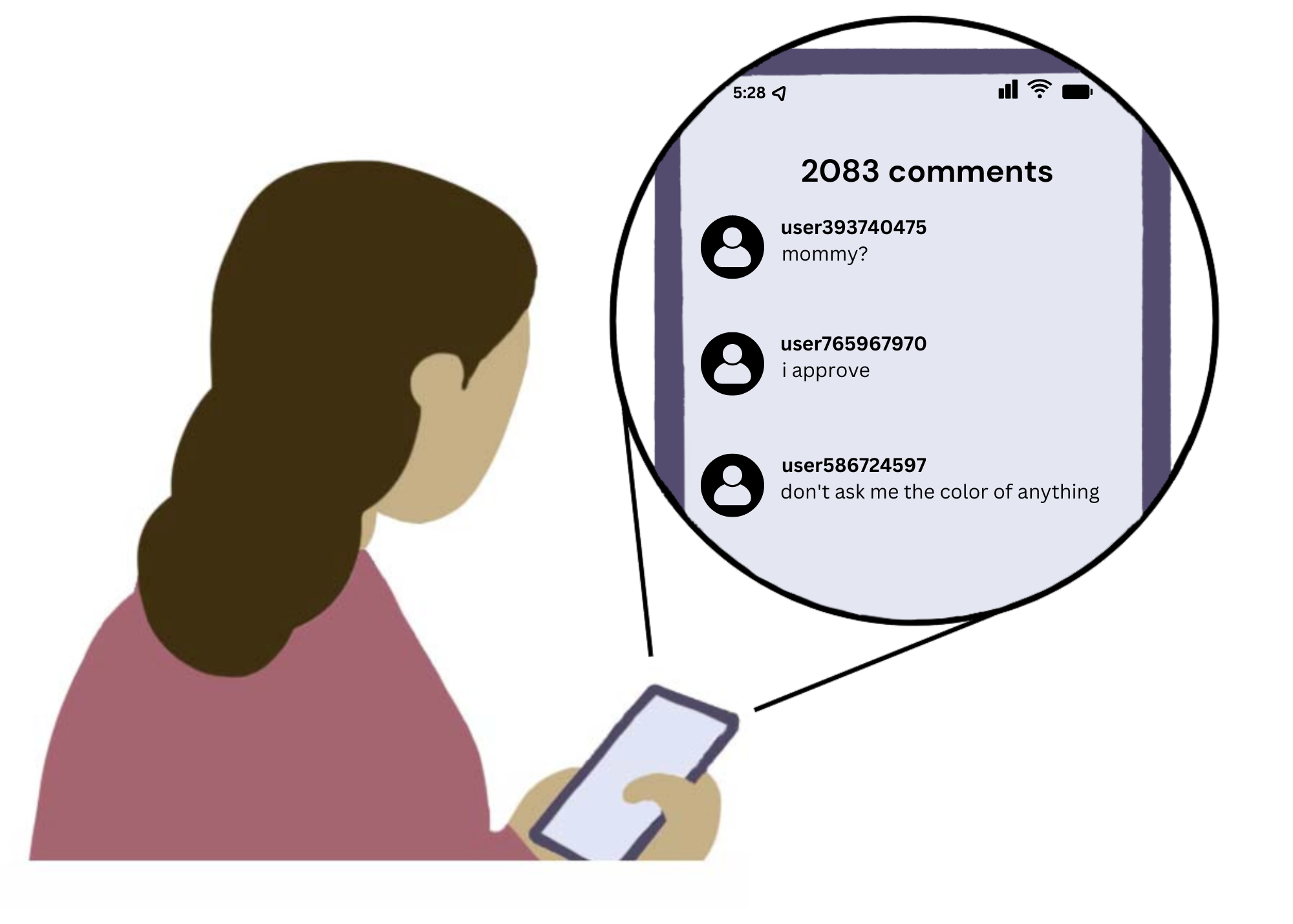

The rise of TikTok in recent years has made it possible for anyone to become an overnight star, yet women and young girls who achieve viral status often face hundreds — if not thousands of comments — within the feedback loop of online misogyny. The illusion of anonymity and encouragement of incel ideology entering the public sphere may be integral to misogynistic harassment on social media, but some still hope for a shift in culture that grants women more respect and their deserved humanity.

General grossness on TikTok

Recent months have seen an increase in TikTok comments under popular videos of women on the platform seemingly referring to the appearance of said women’s genitals — a grotesque amalgamation of judgment and “flattery.” These comments often invite concern given that many of them reference infantilized descriptions of vaginas applied to videos posted by teenagers, resulting in sexual harassment of minors. These unwarranted comments have been reinvented from common phrases to hex codes of colors of female genitalia since early 2021 but reached a fever pitch of popularized harassment in 2022.

These comments stem from a broader societal entitlement to women’s bodies — to comment on them, speculate about them and speak freely and without consequence regarding them. Beyond the concerning implications of such behavior being directed toward and perpetuated by younger generations and teenagers who frequent social media platforms such as TikTok, it opens a myriad of forms of misogyny that enable nameless, faceless individuals online to express themselves in social media spaces that validate their hatred of women.

Gabi Mathus, a sophomore criminology and psychology double major, notes that online behavior can have dangerous real-world implications.

“I think people often give the internet too little credit for [how] it can act as a tool for training people for what is essentially the real world,” Mathus said. “A lot of times really young boys [who are] 12, 13 years old [are] commenting [objectifying] things towards women and [not thinking they will] experience proper repercussions.”

A large part of rape culture as it exists in today’s society is reinforced by language. Social media is one of the primary vehicles of language shared across pop culture, and it holds the power to cultivate norms of casual aggression or objectification towards women with dangerous implications.

Corinne Robinson, a junior political science and international studies double major, is concerned for the growing aggression toward women on social media.

“I do think it’s dangerous for women [to exist on social media] now, especially [knowing that] these men are just not afraid to comment or be aggressive online, so they’re gonna be aggressive in person,” Robinson said. “I don’t doubt that. I think it’s very important for women [and their safety] to be especially conscious and aware of who’s looking at their [posts] and what [those people are commenting]. It’s so much easier to [get] information when you post, [from the background or location on a post.]”

In a culture that permits objectifying language as a norm without repercussions, the behavior and ideology that cultivates it will also thrive. Online forums for “incels” promote violence towards women who object to actions that objectify and disrespect them, furthering concerns about women’s safety on top of societal pressures for their lifestyle and appearance.

Intersectionality in spite of expectations

Though social media comments that mask misogyny as compliments may suggest a false sense of safety from male scrutiny, women who are conventionally attractive still suffer from patriarchal burdens. Unattainable beauty standards are often enforced and rewarded by the algorithms of social media, and objectifying trends on TikTok are no exception. Observers have pointed out that comments such as those used in the “I know it’s pink” trend not only fetishize youth with disturbing casualty, but they also contribute to colorism that disadvantages women of color with increasing relevancy.

Mathus shared that hypersexualization and colorism often overshadow the content women of color desire to produce and their presence online.

“[Often on social media] women of color experience such aggressively sexual comments, and I think that it’s not talked about as much because it’s viewed as a completely separate issue as if [it isn’t an intersectional issue] that needs to be more deeply deconstructed,” Mathus said. “Women of color on TikTok are now having to not post cute [content] or fun [videos] where they’re showing off their outfit because they [fear] those comments. I think that’s a really terrible thing because if they want to do those things, they should be allowed to and not have those comments cross over into the content they create.”

The inherent white supremacy of Western beauty standards can contribute to a culture that hypersexualizes women of color solely for performing femininity in a manner that differs from white women.

Robinson acknowledges that intersectionality is necessary to combat the exotification of women of color.

“There’s this notion that women who aren’t white are ‘exotic,’ and therefore, [many] men feel like they have more power over them,” Robinson said. “[These types of oppression] are all interconnected, [when] you really think about it, and it [comes back to] racist ideologies or sexist ideologies [that] all combine.”

Patriarchal beauty standards are often used to divide and judge women and assign them value based on their appearance, as well as exacerbate double standards for conventional attractiveness that are widely disparate between men and women — not to mention white and nonwhite women. One Twitter user pointed out that many men who left comments describing female genitalia on women’s TikTok videos themselves were all less than desirable and throwing stones from glass houses, or anonymous and judging from behind a blank screen.

Sumaiyah Ryan, a first-year exploratory studies student, succinctly described the double standards of physical appearance that women and men experience.

“[Many] trends in what we see people say [about] women’s appearances online are directly in line with all of these beauty standards and expectations that [society] has for women,” Ryan said. “This carries over into real life too [and] definitely impacts the way that [beauty] trends move because [they’re] what people are [currently] focused on … Beauty is not a requirement of being a man, versus if you wanna be taken any bit seriously whatsoever [as a woman,] you have to be pretty and fit into society’s standards.”

The transparent shield of fame

Similar to everyday women who deal with hate comments from online hate mobs, many female celebrities and public figures receive undue scrutiny and harassment regarding their body solely because of their visibility; such misogynistic criticism often overshadows their work and words.

Many actresses and performers are the subject of hit tweets captioned “I love her necklace,” referring to the prominence of their breasts in images or videos of the women in low-cut clothing, either in costume for a role or walking a red carpet. At many concerts in recent years, fans have taken to calling female artists “mommy” as a result of a viral TikTok sound often used to sexualize unconsenting or unknowing celebrities.

Mathus notes that media attention can exacerbate societal normalization of the sexualization of female celebrities.

“As an avid Marvel fan, I have noted on multiple occasions when listening to interviews that actresses like Scarlett Johanssen or Brie Larson will be asked what their costuming process was like and [if they] were wearing any underwear [under their costumes,]” Mathus said. “Ask them about their performance! [On another interview of an actress speaking] on a red carpet about women’s heart health, all of the comments were about her boobs because she was wearing a slightly lower cut dress. It was just so deeply gross considering the subject matter she was talking about, too. She [was] talking about something serious in the moment.”

Tabloids and message boards still promote the fluctuation of beauty standards as exchangeable with body types, declaring the prominent 2000s “heroin chic” style as “in” for 2023. Many female celebrities such as Ariel Winter have spoken out about how their time in the public eye negatively affected their self-image and self-esteem due to misogynistic criticism and commentary on their bodies. Countless cases of harmful speculation about the bodies of famous women have been debunked by such figures opening up about their disabilities, health concerns and private personal events that resulted in fluctuating weight or appearance.

It has been proven time and time again that needless speculation over the bodies of people one doesn’t know is tacky, unclassy and unnecessary, especially in regard to those of women in the public eye. All celebrities face overexposure and online scrutiny, but women are often used as poster children and derogatory examples of society’s broader judgments on women — their lives, bodies and existence.

The spread of viral sentiments that reflect a general entitlement to comment on women’s bodies often reinforces many of the same patriarchal societal standards women already suffer under; no matter the gender of the person such vitriol comes from, its origins are rooted in misogynistic judgment and oversexualization. In an age of accountability and immensely accessible, deeply embarrassing digital footprints — just be normal online.